preface

Evolving Men or Johns' Customs, v.1

This book was written for the common John and Joan who is at least 20 years of

age. Different people in different epochs wrote down most of the stuff that is

in this book. However, a good idea here and there will show you nothing, as a

touch of a painter here and there will not give you an understanding about the

entire picture. Only when this painter systematizes his touches and put them in

order, only then you will have the total picture.

The purpose of the 1st book is to explain to you the chain of notions

that links the social sciences with the science of the movements of the planets

and the formation of the elementary particles that bind the evolution of man to

Mother-Nature or Father-God. The social evolution is shown through the

examination of the ever-evolving moral values of the upper, middle, and lower

classes. Here I try to clarify to you your long-run interests in this ambivalent

world.

I. The matter of this book

If we wish to

comprehend the universe, we must understand matter – its forms, organization,

movement, and transformation. There is no evidence that thought exists

independently of matter. However, extreme idealists questioned whether the

material world has any objective reality. Bishop Berkeley, one of the best

Platonists, suggested that the physical universe is nothing but a constant

perception in God’s mind.

If we wish to

comprehend the universe, we must understand matter – its forms, organization,

movement, and transformation. There is no evidence that thought exists

independently of matter. However, extreme idealists questioned whether the

material world has any objective reality. Bishop Berkeley, one of the best

Platonists, suggested that the physical universe is nothing but a constant

perception in God’s mind.

What we observe in the universe, is usually reflects and precipitates as our

notion of matter. If you attempt to stop the falling apple, you will feel the

action of what we call a force. Yet, there is no apparent physical connection

between Earth and its part (the apple), because both of them are in the mutual

electromagnetic field. We say that there is an attractive (magnetic or

gravitational) force acting upon them in an electromagnetic field. The word ‘field’

suggests that there is something that permeates these two entities.

Electromagnetic fields have become a common place in our description of nature.

Some physicists talk of matter as being the manifestation of fields.

Matter, as a common expression, comes in the form of four bodies: solid, liquid,

gaseous, and plasmic. Gaseous bodies are the simplest for understanding. We live

in a gaseous body, called atmosphere, which is a mixture of gases, which called

air. We usually become aware of the air by seeing clouds or smoke, so do

the scientists. They usually start from something that appeals to their senses

and then proceed through the cycle of experiments and hypotheses to build a

model that explains the properties of whatever system they are interested in.

The more they know about their subject, the more sophisticated their model

(paradigm) becomes. However, no matter how sophisticated their models are, the

models are no more than an approximation or simplification of reality. We often

lose sight of this fact and confuse our models with reality itself. If our model

of our neighbors would largely ignore their negative characteristics, in other

words, we would refuse to consider and take into consideration their follies,

then, we would have our model as bias as it possible; if our model ignores their

positive characteristics, then, we are prejudicial. In either case, we are not

scientific.

The tendency to forget the simplicity of our models is not unusual in physical

science. Its history has been a continual revolution -- physical laws continue

to be discovered, and old models of the universe give way to new theories.

Sometimes it seems that there is no more room for improvement but this

appearance is, as always, somewhat deceptive. Thus, prejudice and bias start

crippling our ability to think and to understand the real world, starting a new

cycle of improvements in our models.

One of the oldest models is that which was compiled to explain the behavior of

gases. The key to the understanding of gases was the discovery and construction

of the microscope, which allows us to see the microscopic motion of tiny bits of

matter – molecules. Some people thought that we could infinitely divide a drop

of water without changing its quality. However, there comes a stage when the

splitting transforms water into gases. The smallest entity that still has the

quality of water is a molecule of water. There are nearly 2´1023 molecules in a

cubic centimeter of water. This number is so large that the whole solar system

has nearly the same weight in milligrams. You probably know that a water

molecule is expressed using the formula H2O, which is a way of saying that each water molecule

consists of two atoms of hydrogen and one atom of oxygen (later we will consider

atoms)

The smallest bit of oxygen that we can still breathe is the oxygen molecule,

which consists of two married oxygen atoms (O2). If we split an

oxygen molecule in the middle, we would get two atoms of oxygen whose

biochemical and physical properties are dissimilar to those of the oxygen

molecule, as Mistress would become somewhat different when she becomes Miss

again and her rights and responsibilities would be diminished. On the other

hand, ozone (chemical formula O3) can be conceived as

a notorious love triangle with its bitter and passionate qualities.

We use gases to breathe, to make our drinks, to cook, to wage war with animals

and even other people. Each gas is chemically unique, but what is common

to all of them is the movement of their molecules.

In 1650, Otto Von Guericke invented the air pump and showed that light (but not

sound) could travel through space without air. Then Boyle showed that air was

necessary for life (mice died in a glass vessel under decompression) and for

combustion (fires extinguished). In an experiment Boyle trapped a volume of air

in a glass tube and varied the pressure on it. While pressure increases and the

air volume decreases, we must push harder to keep the pump handle in its place.

It looks like we are straggling to compress a steel spring. Boyle recorded the

pressure and the volume of the air in his pump during the experiment. He found

out that doubling the pressure leads to the volume halved. If the pressure

tripled, the volume shrinks to a third. The temperature in his lab was almost

constant and he concluded that for a sample of gas at constant temperature the

pressure multiplied by the volume of a sample was constant (p´v = const). However, this

model works well only under normal, earthly circumstances. If we compress a gas

so that its molecules would be so close to each other that they would have the

new, tenser and denser alliances, this would change their qualities to the

qualities of molecules of a liquid. Then we can double the pressure but the

volume would be almost unchanged. Thus, our models are always relative to the

circumstances in which they were invented.

Molecules in liquid water are about 2´103 times denser than in air. Two vital facts

revealed by Boyle’s experiments: that molecules in a gas are in constant motion;

and that the average speed of a molecule in a gas increased with temperature.

Even in a motionless steel cylinder with carbon dioxide, the gas molecules are

in motion, and not only because the earth is moving together with the cylinder,

but because they have inner centers of gravity and repulsion. There is no such

thing as a motionless molecule or any material body (whatever name we may give

it: galaxy, star, planet, atom, quark, or neutrino). The concepts of

temperature, heat, and energy have a deep connection with molecular and atomic

motion.

How fast do molecules move in a gas? As I mentioned earlier, it depends on the

weight of the molecules and the temperature of their surrounding. (We will

define weight later, but for now, you should believe that weight is

inversely proportional to speed.) Any molecule, from our point of accounting, is

frequently changing its trajectory and speed. From our point of view, it may

take a fraction of a second, but if creatures lived in that molecule, in that

atom, and on that electron, it may very well take millions of their years.

However, we can experimentally measure the average speed of molecules in a gas.

For instance, the approximate average speed of a molecule of helium is 4500

km/hour, of oxygen –1660 km/hour, of carbon dioxide – 1340 km/hour, and the

average speed of Boeing 747—950 km/hour.

If we will raise the temperature of oxygen from 0° C to 30° C, the average speed of the molecules would rise by about

5%. Solar radiation, more correctly, solar light or repulsive energy heats the

earth and the molecules of air get faster. By the way, nobody actually saw the

atoms or even molecules because our instruments use light, but those particles

are moving at almost the speed of light, thus deflecting the external light,

giving us only blotted pictures. On the average, a molecule of oxygen in our

atmosphere is changing trajectory about 6´109 times per second, but an electron completes

about 5´1011

revolutions per second around its nucleus in an atom. It means that about 84 of

their years usually pass before the electron creatures sense the change

of the trajectory of their "solar" system. Calculation shows that in six months

the average horizontal distance traveled by a perfume molecule in a close room

is about 3 meters. Nevertheless, the total trajectory measures about 5.6´1010 m. A bullet is

about 1023 times heavier than a molecule of oxygen, nitrogen, or

carbon dioxide, and therefore, would be unlikely to deviate from its path

sharply. However, it slows by air resistance (that is the cumulative effect a

host of molecular repulsive energies). You can sense a similar resistance if you

try to run through a wheat field.

Newton proposed that the particles (molecules) of air were motionless in

absolute space and held apart by repulsive forces between them; he

analogized the attempt to reduce the volume of a sample of gas with the

compression of springs. He assumed that the repulsive force was inversely

proportional to the distance between the particles (the force would be halving

if the distance would be double). Remember the Boyle's model (p´ v = const).

Based on his

simplistic assumptions Newton showed that a collection of static

particles in a room would behave precisely as Boyle had found. However, Newton’s

model does not explain or predict the other properties of molecules and atoms

because he was very consistent on the assumptions of absolute space and time. He

reasoned that the universe could be analogized with a room filled with stuffed

air, molecules of which are static. Although the earth circles around the sun,

the solar system is immovable, and other suns (stars) are immovable too.

Therefore, he thought that God was something like a frill around the universe,

was something like the room around the stuffed air. Nevertheless, the ultimate

test of any theory concluded in a dilemma whether on its basis, certain

experimental facts, like the moving stars, could be explained and predicted.

Theories have risen and worked out; some of them survive and some -- not. Why

you should believe anything that is said or written, when you know that "seeing

means believing"? How skeptical should you be about something that you cannot

perceive?

Based on his

simplistic assumptions Newton showed that a collection of static

particles in a room would behave precisely as Boyle had found. However, Newton’s

model does not explain or predict the other properties of molecules and atoms

because he was very consistent on the assumptions of absolute space and time. He

reasoned that the universe could be analogized with a room filled with stuffed

air, molecules of which are static. Although the earth circles around the sun,

the solar system is immovable, and other suns (stars) are immovable too.

Therefore, he thought that God was something like a frill around the universe,

was something like the room around the stuffed air. Nevertheless, the ultimate

test of any theory concluded in a dilemma whether on its basis, certain

experimental facts, like the moving stars, could be explained and predicted.

Theories have risen and worked out; some of them survive and some -- not. Why

you should believe anything that is said or written, when you know that "seeing

means believing"? How skeptical should you be about something that you cannot

perceive?

The traders were probably the first known skeptics about the earth. They had

seen too much to believe too much. The general inclination of merchants to these

days to label men as either fools or scoundrels led them to question every creed

and every deed. Thus, mathematics gradually grew up with the complexity of

exchange and astronomy with the increased daring of navigation to find out the

new and more exciting sources of pleasure. The growth of wealth brought the

leisure that is the prerequisite of mental speculation and research. Men now

dare to quest stars not only for guidance on the high seas but also for answers

to the other riddles of their cosmos. Men grew bold enough to attempt reasonable

explanations of processes and events before attributing them to the magical and

super natural forces. Thus, science got into the driver seat. At the beginning,

it was physical; scientists were interested in what was the final and

irreducible state of material things, which were outside of man. From this line

of questioning grew up the materialistic school of thought of Democritus

(460-370 BC), who was probably the first saying that "in reality there is

nothing but atoms and space".

Then came

those who looked at man more closely, looked rather inside the man than outside

of him; they were the traveling teachers of wisdom, the Sophists, who rather

searched the world of thought than the world of things. They asked questions

about every political and religious taboo and boldly subpoenaed every

institution and faith that appeared before their reason. They divided in two

political schools: romantics and classics. The romantics (and Rousseau would be

one of them) argued that nature is good and urban culture – bad, that the noble

savage is better than the civilized man and that by nature all men are created

equal and with a clean mind. Men become unequal only because some of them get

organized into parties and factions, and concoct the laws and institutions to

chain and rule the weak.

Then came

those who looked at man more closely, looked rather inside the man than outside

of him; they were the traveling teachers of wisdom, the Sophists, who rather

searched the world of thought than the world of things. They asked questions

about every political and religious taboo and boldly subpoenaed every

institution and faith that appeared before their reason. They divided in two

political schools: romantics and classics. The romantics (and Rousseau would be

one of them) argued that nature is good and urban culture – bad, that the noble

savage is better than the civilized man and that by nature all men are created

equal and with a clean mind. Men become unequal only because some of them get

organized into parties and factions, and concoct the laws and institutions to

chain and rule the weak.

The classics

(and Nietzsche would be among them) argued that nature is beyond good and evil.

They asserted that by nature men are created unequal and with an inculcated

mind, and that morality and laws are invented by the weak to curb and limit the

strong. Moreover, they also stated that power is the supreme virtue and the most

intense desire of man, and that the hero or superman must rule the world.

However, both schools agreed that of all forms of government, the wisest and

most "natural" is the aristocratic republic.

The classics

(and Nietzsche would be among them) argued that nature is beyond good and evil.

They asserted that by nature men are created unequal and with an inculcated

mind, and that morality and laws are invented by the weak to curb and limit the

strong. Moreover, they also stated that power is the supreme virtue and the most

intense desire of man, and that the hero or superman must rule the world.

However, both schools agreed that of all forms of government, the wisest and

most "natural" is the aristocratic republic.

Such attacks on democracy reflected the rise of a wealthy minority at ancient

Athens. They called themselves the Minority Party, and denounced democracy as

the shameful incompetence that promoted and bred mediocrity. At that time Athens

had 4´ 105

inhabitants, 2.5´

105 were slaves and 1.5´ 105 – citizens. The General Assembly, where

the policies of the State were discussed and determined, was the supreme power

that consisted of all citizens who had the time and courage to gather and carry

out their duties as citizens. The highest judicial body, the Supreme Court,

consisted of over a thousand members, selected by alphabetical rote from the

roll of all citizens. To bribe such a massive court was difficult even for

Cress. Less than 150 citizens had own representative in the judicial and

executive branches of the government, and one of every four citizens was a

representative in the legislative branch. Although the lower class of serfs and

slaves was deprived all rights neither before nor after has humanity achieved

such a remarkable representation of the members of a society in its own

bureaucracy. Nevertheless, the Minority Party of aristocrats asserted that those

democratic institutions of the Athenian State were absurd because they were

inefficient in war and peace.

However, there

were people, who stood on the middle ground. There were such reformists as Plato

and Alcibiades. They not only furnished the satirical analyses of the extreme

democracy but also tried to straighten the wild aristocracies. There was every

school of social thought -- socialists like Antisthenes, who tried to make a

religion of careless poverty; anarchists like Aristippus, who longed for a world

without masters and slaves; and even people, who would like to be worry-free, as

Socrates. Why did the pupils of Socrates revere him so much? It was not only

because he lovingly sought wisdom and truth, but also because he was a great

citizen and friend – with great risk he saved the life of Alcibiades in a

battle. Moreover, he could drink in moderation, without fear and without excess.

Most important, he was a very modest person. His starting point was humble –

"one thing only I know, and that is that I know nothing". However, we know that

when a fool thinks that he is a fool, he is already not a fool. Thus, when

Socrates thought that he knew nothing he already knew something; then, only

modesty prevented him from acknowledging that. Plato said that the oracle at

Delhi had announced Socrates the wisest of the Greeks probably for his modesty

and moderation, but he interpreted this as an approval of his ‘Socratic method’

that starts from knowing nothing, nada, zip, or zero.

However, there

were people, who stood on the middle ground. There were such reformists as Plato

and Alcibiades. They not only furnished the satirical analyses of the extreme

democracy but also tried to straighten the wild aristocracies. There was every

school of social thought -- socialists like Antisthenes, who tried to make a

religion of careless poverty; anarchists like Aristippus, who longed for a world

without masters and slaves; and even people, who would like to be worry-free, as

Socrates. Why did the pupils of Socrates revere him so much? It was not only

because he lovingly sought wisdom and truth, but also because he was a great

citizen and friend – with great risk he saved the life of Alcibiades in a

battle. Moreover, he could drink in moderation, without fear and without excess.

Most important, he was a very modest person. His starting point was humble –

"one thing only I know, and that is that I know nothing". However, we know that

when a fool thinks that he is a fool, he is already not a fool. Thus, when

Socrates thought that he knew nothing he already knew something; then, only

modesty prevented him from acknowledging that. Plato said that the oracle at

Delhi had announced Socrates the wisest of the Greeks probably for his modesty

and moderation, but he interpreted this as an approval of his ‘Socratic method’

that starts from knowing nothing, nada, zip, or zero.

Wisdom seekers like Pythagoras, Heraclitus, and Empedocles had started from

physics (the nature of external things, the laws and particles of the

measurable world). Socrates said, that is OK; but there is a more important

subject for consideration than all those stones, trees, and stars; there is the

mind of man. What is man, and what would he become when he is dead?

Thus, he strolled, nosing about the human soul, uncovering assumptions and

questioning dogmas. If men often mentioned such abstract words like justice,

truth, honor, morality, virtue, or patriotism,

he asked them placidly – what is it? What do you mean by those words with which

you so easily settle the problems of life and death? Socrates loved to deal with

such moral and psychological questions, although men, who were pricked by his

method, his demand for accurate definitions, clear thinking, and precise

analysis, objected to his asking more than he could answer, thus leaving their

minds in greater confusion than ever before. However, that was precisely his

method – if you were really, really stung to the bones by his questions, then,

you would find the road to home. If they did not touch you, if you were not

interested in them, then, you would probably go astray.

Although Socrates asked more questions than he could give answers to, he

positively defined two of our most difficult problems: what is the meaning of

virtue, and what is the best State? These issues are always anew for a new

generation.

The romantics and classics had destroyed the faith of the Athenian youths in the

old moral and customs. There was no more reason for them to study hard, what had

been accumulated by previous generations. Why should not the youths do as they

please, as long as they remain within the frame of law? Such attitude leads to

formal acceptance of laws and customs, but the essence or soul of these laws and

customs is gone. They are no longer their own laws and customs, but are

something that is brought by outsiders, even if those outsiders are their own

ancestors. Furthermore, it leads to a fierce, extreme, and disintegrating

individualism. That is what happened with the Athenian State which had been

weakened by its disintegrating citizens, and left as an easy prey to the

extremely well integrated, communistic Spartans.

What could have been more ridiculous than this passionate, mob-led democracy,

this society constantly debating over its government, these tradesmen and

farmers, who would lead the Supreme Court and the professional generals by

alphabetical rotation? The replies to these questions gave Socrates immortality.

He would not be put on the death row if he tried to restore the polytheistic

faith of the old generations. However, he felt it would be a suicidal policy, a

progress backward, into and not "over the tombs". Now he had his own religion

(ideology), believing in one God and hoping, in his modest way, that death would

not quite destroy him. However, does one's faith carry the lead or can both

ideologies share the common ground in a harmonious chorus? Alternatively, isn't

that more probable that "the divided home cannot stand"? "We cannot know,"

Socrates would say. Nevertheless, he guessed that if he could build a system of

morality (his ideology) that would be independent of religion (the

ideology that is accepted by the majority) and it would be as valid for the

atheist as for the believer. Then, theologies would come and go without

loosening the moral cement that unites the individuals of different interests

into the peaceful citizens of a State.

He always tried to evade extremes, but in this case, he plunged into a gulf of

absolutism, because there is nothing absolute in the world, including the world

itself. Although the world is infinite, infinity is not absolute -- we just

cannot define it. Therefore, there is nothing in the universe that would be

absolutely independent from the rest of the universe. All connects to all;

and we can only speak about degrees of dependency.

Every religion (from Latin, religion means ‘gather together’), every

ideology mixes universal principles with local peculiarities. Principles, if

clear, speak to what is generically human in us all. Peculiarities, rich

combinations of rites and legends, are not easy for outsiders to comprehend. It

is one of the illusions of the extreme rationalism that the universal principles

of religious ideology (which are the social conscious) are more important than

the rites and rituals (which are the social subconscious). Usually the latter

feed the former, and sometimes the process is reversed. To argue that one part

is more important than the other is like asserting that the leaves of a tree are

more important than its roots. The roots would die without leaves, as well as

leaves without roots.

Once a witty person told a story of a man, who climbed to the top of a mountain

and, standing on tiptoe, seized hold of the Truth. Satan, suspecting mischief

from the start, had directed a few of his underlings to tail the man. When the

dickens fearfully reported that despite their efforts the man had seized and was

holding the Truth, Satan yawned and told his servants: "don’t worry, I’ll tempt

him to institutionalize it".

Practical realization of the ideological (theological and metaphysical) truths

always works through institutions, which are constituted by the people and from

the people with their different interests. The interests of the majority are

usually institutionalized as virtues, and their minor interests become

vices. When the interests of the members of the different social classes

would collide and if the quantity and quality of those collisions could be

analyzed, the result can be horrifying. As some witty minds suggested, the

biggest trouble that the proponents of the state religion (the majority's

ideology) should expect, emerges then when their religion (ideology) interferes

with the interests of the different social classes. What should supposedly unite

people could be the bloodiest trench among them. Historically, those ideologies

that were not established and institutionalized by the social classes, remained

disembodied insights of a handful of hermits, which only sporadically boosted

the birth of a new religion. When any religion sifted for its truths, it

appeared as the worldly wisdom. As Thomas Eliot said: "Where is the knowledge

that is lost in information? Where is the wisdom that is lost in knowledge?"

Any ideology confronts the individual with the most precious of everything that

life can present. It calls the soul to undertake the brightest adventure across

the jungles and deserts of our spirit. It calls the individual to confront

reality, to master the self. ‘Know thyself,’ said the oracle of

Delphi to Socrates, and he honestly followed this advice. Wisdom begins when one

learns to doubt his own beliefs and axioms and builds his own ideological

system. If it converges with the common one, then – good for him; if not and it

is more precise, then – even better, because he is at the pinnacle of progress.

Living experience gave you the useful and useless information; thus you became

informed or an erudite. When you have learned how to doubt and handle

this information, then you have knowledge; thus, you became intelligent or

literate. When you applied that knowledge to build your system of the world

and more importantly to live according to it, then you have wisdom; thus, you

became a genius or a scientist.

Translating the notions of "erudite, intelligent, and genius" into a plain

English, you will have "kaka-many smart, street smart, and just smart,"

respectively. A kaka-many smart man knows everything about nothing, a street

smart man knows something about something, and a smart man knows nothing about

everything, except the notion that everything is One. Based on this premise the

smart man can build his own system of the world from scratch.

To build my own system of the world, I need a tool – a method. The scientific

method usually includes inductive and deductive reasoning. I am starting from

the inductive method – gathering a pile of relevant facts and then combining

them into a theory by formulating definitions and explicitly stating the

assumptions. From the summit of my theory I will go with the deductive method,

trying to dissect and disprove my theory. Thus, my system will be crystallized.

So to be, and help me God.

A. Inductive Method

The cradle of science, as we know it, was the Mesopotamian region with its

Sumerian population, from who derived contemporary Iraqis and Syrians. The

simple counting was developed under the pressure of practical needs. The

Sumerians, probably as all ancient men, had started counting from the use of the

fingers and toes to check their goods. The word digit means not only the

numbers 1, 2, 3... but also a finger or toe. Such use of fingers and toes had

developed the decimal system of counting (counting in tens, tens of tens, tens

of tens of tens, etc.). The position of a digit in the number determines the

value it represents, and this value is a multiple of 10, of the square of 10 (10´10, or 102), of the

cube of 10 (10´10´10, or 103), and so

on, depending on the position of the digit. The Babylonians introduced 60 as the

base value; the Europeans used this system until the 16th century

when the Arabs taught them the decimal system developed by the Hindus. The base

sixty system still survives in the division of angles and hours. Computer

science prefers the base eight system as the best for computer languages.

It is not necessary to use 10 as a base. The Maya used to use the base twenty

system, probably combining the fingers and toes of a human being. In fact, it

can be any whole number. If people would have eight fingers on their hands, then

we would probably have the base eight system that need just eight symbols: 1, 2,

3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 0. To indicate the quantity eight we would write 10, where

the 1 now means 1 times eight, just as the 1 in the 10 means 1 times ten. Nine

in the base eight would be 11. Ten would be 12. Sixteen would be 20. Seventeen

would be 21. Sixty-four would be 100 or 1 times (8 times 8)+0 times 8+0 units.

The relevant addition and multiplication tables would change too. Thus, 7 plus 5

would be 14, and 5 times 6 would be 36.

The number zero is required to take advantage of the place value principle,

because there has to be a way to distinguish 708 from 78. The Babylonians used a

special symbol to separate the 7 and 8 in the 708, but did not recognize that

the symbol could be treated as a number. They did not realize that zero

indicates quantity and could be added and subtracted. They did not realize that

zero is not just nothing. If the Yankees have not played with the Marlins, then

the score was nothing. However, if they had played and failed miserably,

then the score was zero.

The ancient Babylonians realized that quality is different from quantity, that

two apples, two boats, and two oxen have common quantity – two. This

development of the idea of quantity as separate from the idea of quality (abstraction)

was the third major invention in the history of humankind after the fireplace

and wheel. Each individual goes through a similar schooling intellectual process

of mentally breaking numbers from their physical objects. You can imagine how

difficult this process has become that even today some nomadic people, while

selling several animals, will not take a lump sum for the herd but must be paid

for each animal separately. They would definitely suspect such a whole-buyer in

cheating.

The Sumerians also invented the four elementary operations with numbers:

addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. In the earliest records of

the Babylonians and Egyptians are already well-developed number systems, some

algebra, and simple geometry. It is probably that the idea of angle came from

observations of the elbows and knees. In many languages, the word for the sides

of an angle is the word for legs. In English, we speak of the legs of a

right triangle, thus bringing into mathematics not only the anatomy but

also the moral. Thus, science became political and politics became scientific.

The Greek word ‘geometry’ means ‘earth measure’ and the

word ‘hypotenuse’ means ‘stretched against,’ apparently against

the two legs of the right angle. For the ancient peoples a plane was just a

surface of a piece of flat land. They were practical people and despite the low

level of their technology, it is amazing how close to ours they came in their

measurements. For instance, the Egyptians knew how to measure the volume of

granaries and they counted the area of a circle as 3.16 times the radius

squared. However, the Egyptians did not develop convenient methods of working

with numbers, particularly fractions. They would reduce a fraction to a sum of

fractions in each of which the numerator was unity. Thus, they would write 7/16

as 1/4 plus 1/8 plus 1/16 before the computation. Consequently, they were not as

good in algebra as the Babylonians. However, they were excellent geometers,

probably because the welfare of the ruling class had been severely dependent on

the just proportion in taxing the constantly changing the land on the banks of

the Nile. Each Egyptian peasant was receiving a rectangle of the land of the

same size and with appropriate taxation. If he would lose some of it due to the

annual overflow of the river, then he should report to his priest who would send

the clerks to measure the loss and make a new apportioning of the peasant’s tax.

On the other hand, the Babylonians were highly skilled irrigators who had dug

canals between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, making to support the thriving

populous cities in that hot and dry climate. Their clay tablets show letters of

credit, promissory notes, deferred payments, mortgages, and the apportioning of

the business profits. They were less politically integrated than the Egyptians

were and consequently relied more on their canals as the means of communication

and on their commercial ties with neighbors comparatively with the Egyptian

reliance on the priesthood and state bureaucracy. The Babylonian ruling classes

had produced not only high quality engineers but also the builders of the

States. Their systems of laws (the code of Ham-Mu-rabi, for instance) were

published nearly seven centuries before Moses "received" his Ten Commandments.

Moses made only some minor adjustments in the code of Ham-Mu-rabi, to

accommodate it to the needs of his semi-nomadic people.

Ham-Mu-rabi emphasized the laws against perjurers as the most severe

transgression against the law and society itself. This system of the laws gives

the prevalence to the rights of society over the rights of individual. From this

system of the laws, the contemporary inquisitorial system of criminal

procedures was derived. Moses only reemphasized the prevalence of the rights of

the society over the rights of the individual. However, he reflected the shift

of interests and he gave the prevalence to the interests of the upper class,

which rather preferred to protect life and property than to say the truth.

Shortly, Ham-Mu-rabi emphasized the ‘don’t lie’ over the ‘don’t kill and don’t

steal’. Moses, on the contrary, emphasized the ‘don’t kill and don’t steal’ over

the ‘don’t lie’. Only the Greeks and Romans, who achieved marvelous success in

building the middle-class, came up with a really new system of laws, from which

derived the contemporary adversarial system of criminal procedures that

gives the prevalence to the rights of individual over the rights of society.

Before the

Babylonian and Jewish (inquisitorial) systems of the laws, there was the

system of private family vengeance (vendettas) in a tribe, in which the victim

of a crime acquired and executed a remedy privately, either personally or

through a family member. Thus, the inquisitorial system of criminal justice was

the direct and extreme response to the system of private vengeance. The

right to initiate legal action against a criminal has been extended to all

members of society (represented by the public prosecutor). The police had been

exclusively bestowed with the pretrial investigative functions on behalf

of society (including the victim and suspect). This exclusive power of the

executive (particularly, military) branch of a government in the extreme

aristocracy tends to turn into the absolute monarchy (like in France under Louis

the XIV). In the case of the extreme democracy, the domination of the

military bureaucracy tends to turn into the totalitarian communistic or

fascistic regimes (like the communism in Russia and China under Stalin and Mao

or like the fascism in Italy and Germany under Mussolini and Hitler).

Before the

Babylonian and Jewish (inquisitorial) systems of the laws, there was the

system of private family vengeance (vendettas) in a tribe, in which the victim

of a crime acquired and executed a remedy privately, either personally or

through a family member. Thus, the inquisitorial system of criminal justice was

the direct and extreme response to the system of private vengeance. The

right to initiate legal action against a criminal has been extended to all

members of society (represented by the public prosecutor). The police had been

exclusively bestowed with the pretrial investigative functions on behalf

of society (including the victim and suspect). This exclusive power of the

executive (particularly, military) branch of a government in the extreme

aristocracy tends to turn into the absolute monarchy (like in France under Louis

the XIV). In the case of the extreme democracy, the domination of the

military bureaucracy tends to turn into the totalitarian communistic or

fascistic regimes (like the communism in Russia and China under Stalin and Mao

or like the fascism in Italy and Germany under Mussolini and Hitler).

Under the inquisitorial system, the prosecutor has the additional duty, besides

the duty to investigative on behalf of society and victim. This additional duty

consists not only in gathering evidence against the defendant, but also evidence

that could prove his innocence. The European inquisitorial system explicitly

prescribes that both sides have full pretrial discovery of the evidence in their

possession. It also mandates that the judge takes an active role not only in the

procedural part of the trial, but also in the fact-finding part. This

concentration of the procedural and fact-finding powers in one hand often leads

to the abuse of power.

On the contrary, the Greco-Roman system of the laws, which bolsters the American

adversarial system of criminal justice, although gives the police the

pretrial investigative functions on behalf of the society, still leaves the

defendant and the private accuser to conduct their own pretrial investigation.

Although the trial could be viewed as a forensic duel between two adversaries,

there is a presiding judge who, at the start, does not know the investigative

details of the case but has plenty of knowledge of the procedural laws, and

there is a jury who are the real fact-finders. Such division of the work of the

court is designed to counterbalance the possible abuse of the judicial power.

The inquisitorial system emphasizes the fact-finding. This system operates on

the premise that in a criminal action the crucial factor is the body of facts,

not the legal rules. It misses the simple anthropological fact that an observer

changes the behavior of the system that is being studied by his own presence in

the system. The social experience shows that the body of facts and the legal

rules has equal importance for social justice and happiness of population.

Historically, the inquisitorial system develops from the system of private

vengeance; and they both complete in the adversarial system of justice. On the

first glance, the adversarial system seems as a backward step in the development

of the social justice system; on the second glance; however, this step was in

the right direction to the Golden Mean Rule, leaving behind the two extremes

of the earlier systems.

I tried to show some implications of the Egyptian and Babylonian science,

because it would be a mistake to look at the practical implications of science

and leave out of sight its ideological implications. Those people who believe

that science has only utilitarian value often neglect or degrade the value of

art, philosophy, and religion. That kind of people thinks that if science was

applied to irrigation, navigation, or calendar creation, then the creation of

science itself was motivated only by the practical (short-sighted) problems.

"After it means because of it," is the type of fallacy they usually make.

By centuries, men (usually from the ruling class who had free time, from making

a living, and could afford to be obsessed with the mysteries of Mother Nature or

Father God) patiently observed the movement of the sun, moon, and stars. These

men gradually overcame the lack of instruments to distill from their

observations the patterns of the heavenly bodies described. These Egyptians and

Babylonians learned that the solar year (the year of the repetitive seasons)

consists of about 365 days. They also observed that the star Sirius appeared at

dawn on the day when the annual flood of the Nile reached Cairo. It probably

took millennia to chart the Sirius’ path in order to predict the next flood,

because their calendar of 365 days was a quarter of a day short of the correct

solar year. After several years, their calendar would no longer predict when

Sirius would appear at dawn. Their calendar would agree with the position of

Sirius again only after 4´365=1460 years; and this Sothic cycle of 1460 years was known to the

Egyptians. Such millennia-long regularities had to be recognized before they

could be practically applied. Once the regularities learned, the people would

live according to them – they would be fishing, hunting, sowing, reaping, and

dancing as the heavens dictated. Moreover, the particular constellations would

get their names according to the activities they forecasted: Sagittarius – the

hunter, Pisces – the fish, Cornucopia – the horn of plenty.

Predictions of the Nile flood or a holiday even a few days in advance required

an accurate knowledge of the movements of the heavenly bodies. The ruling class

of priests, knowing the importance of the calendar for the regulation of daily

life, capitalized on this knowledge to secure their power over the illiterate

masses. The priests probably knew that the real solar year has 365 and 1/4 days

in duration but made secret out of it for the rest of the public. The commoners

would think that the priests had the power over the powers of nature if they

could predict when the commoners should temporarily remove their homes,

equipment, and cattle from the area that would be flooded. The priests would set

it up with the rites and the commoners had to pay for it in the form of tax.

Science and knowledge were, are, and will be the power. From extra-terrestrial

point of view, there is no difference, who has been cashing on the science. The

Egyptian priests capitalized on the knowledge of macro-cosmos; the contemporary

computer wizards and tycoons (the Bill Gates type) are capitalizing on the

knowledge of micro-cosmos. However, from the terrestrial point of view of a

member of a human society, the lack of knowledge breeds the ideological

mysticism in the ruling class, spiritual poverty in the middle class, and

political slavery in the lower class.

It is a common sense to associate the position of the sun, moon, planets, and

stars with human affairs. Our common sense perceives that the crops, mating, and

menstrual periods depend on or are controlled by those heavenly bodies. Thus,

the lack of more precise knowledge leads the proud and cunning priests not to

confess in ignorance but to construct immeasurable and unverifiable theories.

For the Egyptian mystics, their theoretical prescriptions were essential for the

future life of the dead and they accordingly constructed their pyramids and

temples. For instance, the temple of the sun god at Karnak faces directly the

setting sun at the summer solstice. On that day, the sun illuminates the rear

wall of the temple and it is the perfect moment for the priests to display their

power over the natural forces to the simpletons.

The Babylonian mystics were intrigued by the properties of numbers

(particularly, three, six, and seven). They assumed that the universe was

constructed in seven days. That is how we have our week. Their cabala

illustrates how far the mystics were willing to go to explain the cosmic mystery

in terms of numbers. The idea was that each letter of the alphabet should be

associated with a number. Each word was associated with the number that was the

sum of the numbers attached to the letters spelling the word. If two words have

the same number, then they related. This theory was used to make predictions

about someone’s death. If the man’s name coincided with the name of his newly

undertaken enterprise, then, his death could be prophesied.

Because the Egyptians and Babylonians had scanty means of communication, the

ruling class could easily monopolize the sciences in order to make the commoners

revere, worship, and pay them. The ruling class is the state and corporate

bureaucracy. A bureaucracy is always the bureaucracy first, and then, more or

less the monarchical or republican bureaucracy. The restrictions on the means of

transmitting knowledge are the only way to monopolize science that nobody would

be able to challenge the power of bureaucrats. Thus, the Egyptian bureaucrats

had been "destined" to be replaced not by the insider-revolutionaries, but by

the outsider-Greeks who developed the better means of communication (alphabet,

for instance) and science in general. That is why the ruling class is ruling,

because it was able to better organize itself and communicate with each other

(inside and outside of a nation). It is a class because it has an interest

distinctive from the rest of the public – to keep the majority of a nation in

their own disposal.

Sociologists, in general, accepted two basic divisions of humans – by race

and by ethnicity. From physiologists came the notion that human evolution

depends primarily on the physical environment. Therefore, they use a variety of

measuring techniques in their observations, as in archaeology and anthropology,

by examining differences in human physical characteristics. Those sociologists

who draw human evolution primarily from culture and intellect (as the cultural

anthropologists do), emphasize social aspects of human life (such as language,

behavior, and beliefs). Trying to understand human beings and their

organizations, the physical anthropologists classify people according to race –

by visible physical characteristics, such as color of skin, shape of nose, eyes,

ears, and hair. On the other hand, the cultural anthropologists group people

into smaller units, which they call ‘ethnic groups’. The word ‘ethnicity’ is

derived from the Greek word ethnos that literally means ‘nation’.

Therefore, I define the ‘ethnic groups’ as the ex-nationals. The ethnic

groups are the groups of individuals whose ex-nation ceased to exist or it has

no jurisdiction over the territory and people among whom these individuals live

in present. Add to this definition of the ethnic groups my definition of a

nation as a class society, and you have a few starting instruments to work

out your salvation with.

Sociologists include a number of ethnic groups into each racial group. However,

those sociologists are mainly in the service of the upper class; therefore, both

of their distinctions (racial and ethnic) deal with relatively minor differences

among humans. Biologically, all peoples belong to a single species (Homo

sapiens). It is most likely that humans originated in one narrow geographic

area and in a particular distant period. Then, over a very long period, the

earliest people migrated over the Earth taking advantage of land bridges,

climatic changes, and other geologic events. As land areas moved and weather

changed, people in different parts of the world became relatively isolated. A

process of selection gradually caused each group to develop protective physical

characteristics and social organization suitable to the survival of a group in

its particular environment. And the leaders of these "ethnic" groups usually use

those minor physical variations of the members of the different groups as the

basic mean to discern "own" from "strange", "alien", "foreign". Thus, they used

to use to divide people and to instigate hatred between them. ‘Divide and

conquer’ was, is, and will be their motto. Therefore, you, commoners, better be

knowledgeable about their main weapon and be preparing to stand your own ground

if you do not wish to be the "innocent" dupes and the ‘cannon fodder’ in their

schemes.

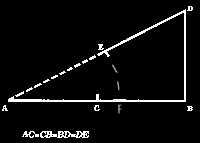

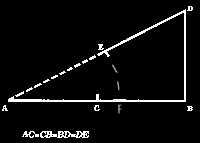

Too much has been said about the profundity of the ancient peoples and their

marvelous temples and pyramids. However, most scholars agreed that the Egyptian

and Babylonian scientists had one major defect, namely – their conclusions were

based on the purely inductive method. For instance, if an Egyptian clerk was

ordered to divide an area of a land into 100 square meter parcels, shaped in

rectangles, and with the cost of fencing as low as possible, then what would be

his modus operandi? He would probably lay out a rectangle with 100 square meters

of area by using such dimensions as 50 by 2 with 104 meters in perimeter, then

25 by 4 with 58 meters in perimeter, then 10 by 10 with 40 meters in perimeter.

He needed to find out the smallest perimeter. Since the possibilities were

infinite, he could never try them all; so, he could not determine the best

choice. The clerk could suspect that the square 10 by 10 meters has the smallest

perimeter, however, he would not be sure that it is so. His trial-and-error

method with proceeding from one experiment to another and gathering facts that

would lead him to a likely conclusion that of all rectangles with 100 square

meters of area the 10 by 10 meters square has the least perimeter. His

experience with rectangular areas would support his conclusion, and he would

probably pass it down to posterity as a veritable, reliable, scientific

fact. But what about rectangles with area of 50, 175, 320, 1410, and so forth,

square meters? Would he do the experiments repeatedly? This method of proving

something is very, very time-consuming. Actually, such a method stimulates our

patience, not our genius.

Essentially, the inductive method consists in proceeding from a simple idea to

the complex one or in concluding that something is always true based on a

limited number of experiments. Suppose a person has had bad experiences with

dentists, and he concludes that all dentists are horrible people. So, his

conclusions, obtained by inductive reasoning, appear based on facts; however,

they are not established beyond reasonable doubt because there is always a

possibility to find the fine, decent, and skillful dentist. There are some

limitations to inductive reasoning. For example, living in New York, we cannot

inductively conclude what the effect might be of a nuclear bomb being detonated

on top of us. We also cannot inductively conclude what effect it may have on the

entire society if our legislators adopt an untried law.

Inductive reasoning can follow many routes, and the common one is by analogy.

For instance, the Egyptians believed in immortality, but they did not conceive

the soul as something that might be separated from the body. Thus, they reasoned

by analogy that if a living person needed food, drinks, clothes, and tools, so

did a dead one. Therefore, they accordingly stuffed their tombs with those

things. Reasoning by analogy is useful, but it is long way from observing squids

to the construction of rockets. Reasoning inductively or by analogy might be

based on the facts of experience and might be entirely correct; however, the

obtained conclusion is not certain or beyond reasonable doubt. If the certainty

is indispensable (as it is in the case when we would like to know beyond

reasonable doubt if an airplane with 500 passengers on board would fly or fall

to earth), then the inductive methods have little practical merits.

Nevertheless, there is a method of reasoning, in which the Greeks made a solid

deposit and, with which today, we can be sure beyond reasonable doubt in our

conclusions. And this type of reasoning is usually known as 'deduction'.

B. Deductive Method

The scientists that lived before the Greeks used the inductive method in their

reasoning. Most of the early Greek scientists were immigrants from Asia Minor,

which is situated between Mesopotamia and Egypt, and thus acquired and

transmitted their culture and science farther. The Greeks produced a radically

different culture and science because of their severe reaction against the

Babylonian and Egyptian influence. A millennium-long experience is no doubt a

good teacher, as it is in medical practice or in breeding, but it is not a

brilliant one. The method of trial-and-error can be useful because it is a

time-consuming one. Sometimes it can be even disastrous (as it was with the

Persian naval armada that was crushed by a storm, thus preventing an invasion

into Greece, causing the angry king Cirus to order his troops to flog the sea,

thus admitting the inferiority of his knowledge of ruling).

Let us proceed with the Greeks. They reasoned that if an individual accepts the

obvious facts of life, for instance, the facts that all food decays and

that an apple before him is a food, then, he must conclude that the apple

will someday be rotten. He might also argue deductively that if he had premises

that all sages are intelligent and that no intelligent person would mock

knowledge, then his inevitable conclusion would be that no sage mocked the

science. In this stage of reasoning it makes no difference weather we agree with

the premises (axioms) or not, what matters is that if you accept the axioms, you

must accept the conclusion. Because if you start questioning your axioms (does

knowledge equal science? Is any knowledge science? Is the

knowledge of rites or astrology is science?), then you lost your faith into the

obviousness of the underlying facts. In short, the deduction is

reasoning that starts from a few principles and moves from the whole picture

(expressed in those underlying principles) to its parts (details).

Deduction, as a method of arriving to the 99.99…percentage full-proof

conclusions, has many advantages over induction. In contrast to induction

and experimentation, our conclusion is our truth, and it comes with our surety

in our premises. The deductive or theoretical method can also be implemented

without expensive instruments or loss of such. Before we can build a rocket, we

can apply the theoretical reasoning and decide the outcome. In the calculations

of astronomical distances, deduction is the only available method, because we

cannot apply a measuring line to the stars.

Despite all those advantages, theoretical reasoning (deduction) does not

supersede experimental reasoning (induction), because there is not a single

axiom that we cannot question. However, life goes on and for the most practical

purposes a high degree of probability, say, above 95% or beyond reasonable

doubt, may suffice.

Both of these scientific methods have their advantages and disadvantages.

Nevertheless, the Greeks insisted that all our conclusions be established by

using the deductive method. The Greeks were discarding all procedures, rules,

and formulas that the preceding urban cultures had produced by using the

inductive reasoning. Why did they do so? The answer to this question may be

found in the organization of the Greek society. Their scientists (philosophers,

artists, mathematicians, architects, and engineers) were members of the ruling

class, who regarded manual labor and commerce as unfortunate necessities. The

Pythagoreans boasted that they had raised arithmetic, a commercial tool, above

the needs of merchants. Plato and Aristotle declared that the trade of a

shopkeeper or mechanic is degrading for a free man and should be a crime.

Moreover, the Spartans and Boeotians actually had a law for those who defiled

themselves with commerce – they were excluded from the state office for ten

years.

The Greek attitude toward manual labor and commerce grew from a streak of

successful wars, in which they acquired a multitude of serfs and slaves. Now

slaves ran the households and businesses (manual and technical jobs, and even

such professions as medicine). Thus the slavery, deepening deep between upper

and middle classes, fostered the split between theory and practice, and

bolstered the development of the abstract and speculative part of science,

neglecting experimentation and practice. If you look at the present American

middle class, as its members preoccupied with commerce and industry, and again,

they prefer excessive inductive reasoning, then, it will not be hard to

understand the reaction of the upper class Greeks and their insistence on the

exclusivity of deduction. Their insistence on the theoretical method of

thinking removed the science from the artisans’ shop and the farmer’s shed.

Hence, it would be our reason that would decide what is the truth, not our

senses. Thus, the Greeks revealed to humankind the importance of our mental

powers.

The Greeks redeveloped a taste for analysis, for mental vivisection of material

objects. They followed in the riverbed of the ancient Aryan beliefs, discerning

the soul (psyche) from the body (soma). They were deeply concerned

with the problems of life and death, good and evil. Their reasoning circled

about broad generalizations. Even today, it is difficult to experiment with

souls; hence, they preferred the theoretical method of arriving at truths. The

Greeks preferred the abstract thinking because it appeared to them as something

permanent and perfect in the world of corruptible and imperfect material

objects. For them, the abstract man became more important than the real men did.

It means that the idea of reality becomes more important than reality itself.

Just as the structure, interval, and counter-point had become more important

than the music itself.

The Greeks began to perceive beauty as order (definite shape,

consistency, and completeness). Beauty became not simply an emotional

experience, but mainly an intellectual one. Reason prevailed over emotions. The

contemporary system of criminal justice finally prevailed over the system of

private vengeance. Pericles, in his famous speech, praised the Athenians who

died in the battle at Samos not only because they were courageous, but mainly

because their reason dictated them to be patriotic and protect the life,

liberty, and property of their compatriots. The abstract ideas such as

Intelligence, Justice, Beauty, Virtue, Honor, Order, State, Cosmos, and Nature

were to the Greeks as the cabala was to the Babylonian mystics and as the

essence of nature (God) would become to the Christians. They did not understand

the abstractness of those notions and perceived them as real as the feeling that

the earth was flat. For them, justice was something that was acting on its own

and if people would listen to it or would repeat the word ‘justice’ long enough,

then all would be right. Our daily affairs are not worthy of the attention of an

intelligent man but his duty is to use his mind to clarify the ideas of Truth,

Justice, and Goodness. These idealizations are the essence of the Plato’s

ideology and are on the same level as the abstract mathematical ideas.

C.Plato’s Republic

It was a turning point for Plato when he had met Socrates. Plato had been

brought up in an upper class family; he was handsome, vigorous, and an excellent

soldier. Despite his youth, Plato had found a joy in the ‘dialectic’ games of

Socrates. It was a delight to look at the master puncturing and deflating the

old axioms and dogmas. Plato had entered the sport of the sharp questions under

the guidance of the old gadfly, as Socrates liked to call himself. He had

passed from mere debate and discussion to careful analysis. "I thank God," he

used to say, "that I was born Greek and not barbarian, freeman and not slave,

man and not woman; but above all, that I was born in the age of Socrates." The

tragic death of the latter finished the quiet life of Plato. Later Plato wrote

an apology or a defense of his teacher, in which the best known martyr of

ideology proclaimed the rights and necessities of free and unfettered thought,

asserted his social values, and refused to beg for mercy from his ideological

foes. Socrates thought that he could teach them to see their real interests

clearly, to see the distant results of their present deeds, by criticizing

their desires and channeling their chaotic short-range interests into a

long-lasting social harmony. He thought that the intelligent man might have the

same violent and anti-social impulses as the ignorant man, but the former would

control them better and slip less often into the animal state than the latter.

In a

rationally administered society, the individual (probably, the ignorant one)

would receive more powers than he gave in when he surrendered some of his

liberties, and the advantage of every man would depend on loyal conduct

(probably, to his neighbor). Then only clear sight would be needed to ensure

peace and order. But if the government is irrational and chaotic, if it rules

without helping, and commands without leading, then how is it possible to

persuade the self-seeking individual to obey the laws and confine his interests

within the common Good? And what is the "common good"; who will define it? The

mob usually decides the important issues in haste, thus, leaving out of

consideration some of the important facts, only to repent about it in the

aftermath desolation. Is it not usual that men in crowds are more foolish,

violent, and cruel than separated men? Mere numbers rarely gave wisdom. It is

more probable than not that the management of a State requires the sober thought

of the finest minds. Then, how can people be safe and strong if their sages do

not lead them?

In a

rationally administered society, the individual (probably, the ignorant one)

would receive more powers than he gave in when he surrendered some of his

liberties, and the advantage of every man would depend on loyal conduct

(probably, to his neighbor). Then only clear sight would be needed to ensure

peace and order. But if the government is irrational and chaotic, if it rules

without helping, and commands without leading, then how is it possible to

persuade the self-seeking individual to obey the laws and confine his interests

within the common Good? And what is the "common good"; who will define it? The

mob usually decides the important issues in haste, thus, leaving out of

consideration some of the important facts, only to repent about it in the

aftermath desolation. Is it not usual that men in crowds are more foolish,

violent, and cruel than separated men? Mere numbers rarely gave wisdom. It is

more probable than not that the management of a State requires the sober thought

of the finest minds. Then, how can people be safe and strong if their sages do

not lead them?

Woe to him who teaches men faster than they can learn. However, Socrates’ tragic

death conceived Plato as a new thinker (as any death bears a new life in

itself), because it filled him with such a hatred (that bears love in itself) of

the mob that even his aristocratic lineage should hardly be responsible for it.

Plato concluded that extreme democracy must be replaced by the rule of

the wisest. How to find this wisest man and how to persuade him to rule – became

the all-absorbing idea of Plato. He went to Egypt and was shocked by the ruling

priests who scorned Greece as an infant-state, without stabilized traditions

(profound culture) and, therefore, unworthy yet to be taken seriously. Shock is

the best teacher; thus, the lesson of the ruling clerical bureaucracy of the

stagnating agricultural nation was reflected, and it is playing prominent role

in Plato’s Utopia. Then he sailed to Italy, joined the Pythagoreans, and learned

how a small group of men, living a plain life, could be ruled by the wisest. He

wandered for twelve years, imbibing every creed from every source that he could

find. A man of forty now, he returned to Athens and founded his Academia. He

lost a little bit of his youthful enthusiasm and gained the mature and real

perspective, in which every optimistic or pessimistic thought,

every extreme was perceived as a half-truth. He created for himself a

medium of expression in which both Beauty and Truth might find space and time to

play – the dialogue. His love for jest, irony, and metaphor leaves us at times

baffled in which character of a dialogue the author speaks. But, hey! That is

the beauty of his writings, in which he leaves the space and time for our

imagination, as the best Bibles usually do.

Of course, Plato has some of the qualities, which he condemns. On the one hand,

he complains against poets and their myths, on the other hand, he creates the

new myths himself. He scolds the priests who preach hell and offer redemption

from it in exchange for something material; however, he is a priest and moralist

himself. He condemns the phrase-mongering disputants (the Sophists) for chopping

logic and slipping into comparisons, but he slips and chops himself. Let see how

a parodist mocked him: "The whole is greater than the part? – Surely. – And the

part is less than the whole? – Yes. – Therefore, clearly, philosophers should

rule the State. – What is that? – Isn’t it evident? Let’s go over it again."

Despite all of that, his Dialogues (and his Republic is the best among

them) remain the best seller of the world, because here we can find the clearest

questions (a good question is a half of its answer) for contemporary problems in

communism, environmentalism, feminism, abortion-control, teenage-pregnancy, and

liberal education. Therefore, let us temporarily think like an extremist (caliph

Omar) who cried about Koran: "Fidels, burn all the libraries, for their

value is in this book alone!"

1. Plato’s Problems

In his Dialogues, Plato uses many names, but usually his mouthpiece is Socrates;

his counterparts I will call – the Sophist. In the Representative Men,

Socrates asks the Sophist: "What do you consider to be the greatest blessing

which you have reaped from wealth?" The Sophist answers that wealth enables him

to be generous, honest, and just. Then Socrates asks him what he means by

Justice; for nothing is more difficult than to give and clarify a definition.

Then Socrates breaks all offered definitions until the Sophist blows his top

with a roar: "if you wish to know what Justice is, you should answer and not

ask, and should not pride yourself on refuting others... For there are many who

can ask but cannot answer". Nevertheless, Socrates continues to provoke him and

the angry Sophist gives the next Nietzschean definition:

"Listen, then, I proclaim that might is

right, and Justice is the interest of the stronger... The different forms of

government make laws, demo-cratic, aristo-cratic, or auto-cratic, with a view to

their respective interests; and these laws, so made by them to serve their

interests, they deliver to their subjects as ‘justice’, and punish as ‘unjust’

anyone who transgresses them... I am speaking of injustice on a large scale; and

my meaning will be most clearly seen in autocracy, which by fraud and force

takes away the property of others, not retail but wholesale. Now when a man has

taken away the money of the citizens and made slaves of them, then, instead of

swindler and thief he is called happy and blessed by all. For injustice is

censured because those who censure it are afraid of suffering, and not from any

scruple they might have of doing injustice themselves."

In the Gorgias, the Sophist denounces

morality as an invention of the weak to neutralize the strong.

"They distribute praise and censure with a view to

their own interest; they say that dishonesty is shameful and unjust

– meaning by dishonesty the desire to have more than their neighbors; for

knowing their own inferiority, they would be only too glad to have equality...

But if there were a man (like the Nietzschean Superman) who had sufficient

force, he would shake off and break through and escape from all this; he would

trample under foot all our formulas and spells and charms, and all our laws,

that sin against nature... He who would truly live ought to allow his desires to

wax to the uttermost; but when they have grown to their greatest he should have

courage and intelligence to minister to them, and to satisfy all his longings.

And this I affirm to be natural justice and nobility. But the many

cannot do this; and therefore they blame such persons, because they are ashamed

of their own inability, which they desire to conceal; and hence they call

intemperance base... They enslave the nobler natures, and they praise justice

only because they are cowards... This justice is a morality not for men

but for foot-men; it is a slave-morality, not a hero-morality; the real

virtues of a man are courage and intelligence." Plato,

Republic (p. 336-344), Gorgias (p. 483).

"Let us consider what will be their [the communards, VS] way of life

[definitely, not gay, VS].... Will they not produce corn, and wine, and clothes,

and shoes, and build houses for themselves? And when they are housed they will

work in summer commonly stripped and bare-foot, but in winter substantially

clothed and shod. They will feed on barley and wheat, baking the wheat and

kneading the flour, making noble puddings and loaves; these they will serve up

on a mat of reed or clean leaves, themselves reclining the while upon beds of

yew or myrtle boughs. And they and their children will feast -- drinking of the

wine, which they have made; wearing garlands on their heads; and having the

praises of the gods on their lips. They will live in sweet society, having a

care that their families do not exceed their means; for they will have an eye to

poverty or war.... Of course, they will have a relish – salt, and olives, and

cheese, and onions, and cabbages or other country herbs which are fit for

boiling. And we shall give them a dessert of figs, and pulse, and beans, and

myrtle-barriers, and beech-nuts, which they will roast at the fire, drinking in

moderation. And with such a diet they may be expected to live in peace to a good

old age, and bequeath a similar life to their children after them." Plato,

Republic, p. 372.

Here we can perceive Plato’s concept of population

control (by the infanticide of the feeble, on the Spartan manner), the

vegetarianism, and the ‘back-to-nature’ motive. However, Plato is not a naive

teenager to rest upon this idyllic picture. He asks himself a question: "Why is

it that such a simplicity or this Utopia has never come?" He answers – because

of greed and luxury, because men are not satisfied with a simple life. They are

jealous, competitive, acquisitive, and ambitious. They soon tire of what they

have, and desire for what they have not. The result is the encroachment of one

group upon the territory of the rivals. A war begins. The new necessities

quickly display, and demand is high. To supply the army, trade and finance

develop, bringing a sharp class division. – "Any ordinary city is in fact two

cities, one that city of the poor, the other of the rich, each at war with the

other." An industrious middle class arises; its members seek higher social

positions through new wealth – "they will spend large sums of money on their

wives". The new distribution of wealth leads to political changes – wealthy

traders and bankers prevail over the land-owning aristocracy and rule the State.

Thus, aristocracy gives way to plutocracy (from Greek, ploutos means

‘wealth’ and crates – ‘rule’).

Every form of government tends to perish by excess of its basic

principle. Aristocracy ruins itself by the excessive limiting of the

inner circle of power. Plutocracy ruins itself by the excessive scramble

for immediate wealth, mired in the successive row of corruption scandals. In

either case, a revolution comes. When a body is weakened by neglected ills, the

merest exposure may bring serious disease. So does the revolution; it may spark

from a slight and petty occasion (like the French revolution, which sparked from

the petty joke of the queen – "If the people have not enough bread, let them eat

cakes".) Although a provocation may be petty, the causing wrongs are always

strong and the result is always grave. Then the excessive democracy comes

– the poor overcome their opponents, slaughtering some and banishing the rest.

Although the extreme democracy gives the people an equal share of freedom

and power for a short period, it also ruins itself by the insistence on its