egyptians

4. The Egyptians

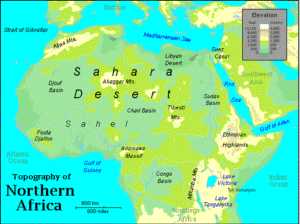

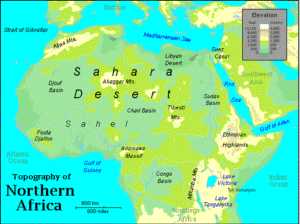

Archaeological records show that

the horticulturists of the Nile had settled in the long and narrow valley of

this river about seven millennia ago. Herodotus called Egypt "the gift of the

Nile", for without it, the place would be a sandy desert. The Nile flows

northward for nearly 6.5 thousands km from central mountainous Africa to the

Mediterranean Sea. When the season of rains had been coming to central Africa,

the Nile had overflowed its banks and deposited a fertile layer of soil, which

could support a numerous gardening population.

Archaeological records show that

the horticulturists of the Nile had settled in the long and narrow valley of

this river about seven millennia ago. Herodotus called Egypt "the gift of the

Nile", for without it, the place would be a sandy desert. The Nile flows

northward for nearly 6.5 thousands km from central mountainous Africa to the

Mediterranean Sea. When the season of rains had been coming to central Africa,

the Nile had overflowed its banks and deposited a fertile layer of soil, which

could support a numerous gardening population.

The early prehistoric dwellers on the Nile inhabited the terraces or plateaus

left by the river as it cut its bed. The remains of their tools and implements

show their gradual development from hunters and gatherers to settled gardeners.

Evidence of organized settlements has been found mainly in their cemeteries. The

artifacts, produced during that time, were put into the grave with the body for

the use of the spirit in the next life, thus preserving a great quantity of such

personal goods as pottery, tools, and weapons. The pottery was often decorated

with painting that reflects the life of the time. Images of birds and animals

common to the land bordering the Nile abound, and from the latter part of the

prehistoric (pre-dynastic) period come elaborate depictions of many oared-boats.

At the beginning, most of their implements, the gardeners of the Nile chipped

from stone; later, they more often used copper for beads and simple tools. They

used cosmetic palettes (made of stone) for grinding eye paint, and carved small

sculptures and figurines from ivory or modeled them in clay. Gold, copper,

stone, and other natural resources were abundant along the riverbed. Within two

millennia, the Nile gardeners learned how to control the river and they had

built some irrigation systems.

They were tribal and locally minded, but their wealth was growing and capturing

the imagination of the neighboring pastoralists. At about the 31st

century BC, the Semitic nomadic tribes from the mountainous region of

present-day Syria and Lebanon conquered the Nile delta, and then expanded south

into Nubia and north as far as Syria.

The history of ancient Egypt is usually divided into three large (half of a

millennium) periods of stable ruling and corresponding small (a couple

centuries) transitional periods of civil wars and following nomadic invasions

(the Egyptian Dark Ages – when the changes of the upper class and its language

occurred). The Old Kingdom or Pyramid Age continued from 2686 to 2181 BC, the

Middle Kingdom (2040-1786 BC), and the New Kingdom (1570-1085 BC).

The Egyptian State building followed the pattern and practice of the

Mesopotamians but in a slower pace. The slower development of the Egyptians was

based on the geography of the country, which had been united by the Nile and, at

the same time, semi-isolated from outside cultural influences by the vast

deserts. This semi-isolation fostered a slower and more continuous artistic and

language patterns, because the new waves of the nomadic invasions (and

corresponding changes of the upper class and its language) rarely reached Egypt.

Egyptian has a longer recorded history than any other language, for nearly five

millennia. It is the only member of the Hamitic linguistic family, which include

Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian, Late Egyptian, Popular Egyptian and Coptic. Words

in Old Egyptian, as in following Egyptian languages, tend to be formed from

roots typically consisting of three consonants. The stable meaning of the root

is altered by different vowel patterns. However, forms of verbs and the Old

Egyptian syntax vary markedly from forms of verbs and syntax of the following

Egyptian languages. Spoken and literary Old Egyptian differs considerably. Most

of the formal inscriptions on tombs, temples, pillars, and statues were written

in Old Egyptian, and approximations of living speech are preserved only in

practical documents such as business records and letters.

Based on the existing literary evidence the Hamitic linguistic family has been

divided into five eras. Old Egyptian (the 30th through the 22nd

centuries BC) was the written language of the Early Dynastic Period through the

Old Kingdom (0-6th Dynasties). The classical Egyptian literary

language is believed to reflect the speech of around the 22nd century

BC. Middle Egyptian was dominant from the 20th through the 13th

centuries BC. Late Egyptian began to develop during the 2nd Dark Age

and came into general use in the New Kingdom (the 15th through the 10th

centuries BC). Middle Egyptian had been used by the 18th Dynasty (the

first dynasty after the 2nd Dark Age) and was still used in

monumental inscriptions in the 4th century BC (under the Persians).

The speech of the 15th century BC shows markedly grammatical and

phonetic changes from the earlier language. In the 7th century BC,

during the Late Period, Popular (Demotic) Egyptian became the accepted

literary language and remained so through the Persian, Greek, and Roman

domination of Egypt into the 4th century AD.

Popular Egyptian was written with a distinctive cursive script and represented

the speech of around the 7th century BC. The last era of the Egyptian

language was Coptic, which was initially in use concurrently with Popular

Egyptian. It was written in Greek characters, with additional seven signs from

Popular Egyptian for sounds not common to Greek. Beginning with the 3rd

century AD, it was used for Christian literature. Between the 8th and

the 14th centuries, the Arabic language gradually supplanted Coptic.

The latter is still in use today as the liturgical language of the Christian

Coptic Church.

The Egyptians developed three forms of writing: hieroglyphics, and two

cursive scripts (hieratic, and popular). Hieroglyphic

writing is pictorial writing, used for formal inscriptions. Hieratic

cursive was used before Egypt’s conquest by the Semitic Assyrians, c. 650 BC,

and popular cursive was used between 650 BC – 450 AD. All three used to

use ideograms, syllables (consonants only), single letters, and determinatives

(interpretive aids for signs having more than one meaning). The writing, as in

the Semitic linguistic family, did not represent vowels, and thus (except for

Coptic) scholars could trace the phonetic evolution of the language only through

consonants. After the popular cursive, Byzantine Greek was in use. The latter

was supplanted by Arabic script.

Through each epoch, we will follow from the "hard" evidence of rocks and metals

to the "soft" evidence of Egyptian literature, which is characterized by a wide

diversity of types and subject matter. From early times, the Egyptians used to

use such literary devices as simile, metaphor, alliteration, and punning.

The scientific literature of ancient Egypt includes legal, administrative, and

economic texts; hymns to the gods; mythological and magical texts; instructive

literature, known as ‘wisdom texts’; extensive collections of mortuary texts;

and scientific treatises, including mathematical and medical texts. The popular

literature includes stories, poems, biographical and historical texts, and

private documents such as letters. Some authors of several compositions dating

from the Old and Middle Kingdoms were revered by the later generations of the

Egyptians. However, most of these authors came from the educated upper class of

government officials, and what they wrote was meant to be read by educated

bureaucrats. Indeed, many school-texts of the Middle Kingdom were composed as

political propaganda, to teach (or better say, to brainwash the students who

learned to read and write by copying these texts) to be loyal to the ruling

dynasty.

Before the Egyptian State emerged,

the Neolithic gardening settlements of the Nile were concerned with the raising

of vegetables, grains, and animals. These settlements slowly gave way to larger

groupings of people. When the Nile gardeners became able to produce enough

surpluses for maintaining a large bureaucracy and the need to control the Nile

floodwaters through big dams and canals had increased, the necessity eventually

led to the emergence of city-states. The multiplied Semitic pastoral tribes, in

order to survive, conquered several of the city-states in the Nile delta,

stabilized the central government, thus creating the new agricultural society –

the Egyptians. In a couple centuries, a new Egyptian society was organized and,

by the 29th century BC, the Egyptian upper class was firmly

established. The centralized bureaucracy was at work, handling a large and

well-trained army and organizing the construction of irrigation systems and

pyramids (kings’ tombs) on a large scale that required the cooperative efforts

of millions.

Before the Egyptian State emerged,

the Neolithic gardening settlements of the Nile were concerned with the raising

of vegetables, grains, and animals. These settlements slowly gave way to larger

groupings of people. When the Nile gardeners became able to produce enough

surpluses for maintaining a large bureaucracy and the need to control the Nile

floodwaters through big dams and canals had increased, the necessity eventually

led to the emergence of city-states. The multiplied Semitic pastoral tribes, in

order to survive, conquered several of the city-states in the Nile delta,

stabilized the central government, thus creating the new agricultural society –

the Egyptians. In a couple centuries, a new Egyptian society was organized and,

by the 29th century BC, the Egyptian upper class was firmly

established. The centralized bureaucracy was at work, handling a large and

well-trained army and organizing the construction of irrigation systems and

pyramids (kings’ tombs) on a large scale that required the cooperative efforts

of millions.

From early times, the Nile gardeners believed in a life after death. This belief

dictated to the alive that, the dead should be buried with material goods to

ensure well being of the dead, who, in their eternity, became the gods. It was

implied that reciprocity of the dead would follow and they would care (from

below) for the alive. The regular patterns of nature (the annual flooding of the

Nile, the cycle of the seasons, and the progress of the sun, moon and planets

that brought day and night) were considered gifts of the gods for the people of

Egypt. The Egyptian culture was rooted in a deep respect for order and balance

of nature. Change and novelty were not considered important in themselves;

consequently, Egyptian art was based on relatively rigid tradition. Manners of

representation and artistic forms were worked out early in Egyptian history and

were used for more than three millennia. The art styles were so rigid because

the primary intention of the Egyptian artists was to reflect the content of the

object (a living creature or a thing), not its form. They tried not to create an

image of an object as it looks to the eye of a living human being, but rather to

express the truth (the essence) of this object. They tried to imaging how it

would be in its eternity. That is what the meaning of the Latin word ‘art’

is.

1) Old Kingdom

The Egyptians considered their king (pharaoh) as more than just a

human being because they believed that the king was responsible for ensuring

compliance with a divine order for the universe. Because the king was considered

as the total embodiment of the clerical and state bureaucracies, art (in its

main forms) was devoted principally to royal service. Thus, the links between

divine and earthly power were expressed in many ritual objects. One of the

ritual objects (made about 31st century BC and decorated on both

sides in low relief) was commemorated to the victory of King Narmer’s northern

army over his southern enemy. On one side of this carved stone palette, the king

(wearing the crown of the north) is shown behind his troops that are marching on

the enemy and defeating it. On the other side, Narmer (wearing the captured

crown of the south) is shown subjugating the leader of the south.

The Egyptians considered their king (pharaoh) as more than just a

human being because they believed that the king was responsible for ensuring

compliance with a divine order for the universe. Because the king was considered

as the total embodiment of the clerical and state bureaucracies, art (in its

main forms) was devoted principally to royal service. Thus, the links between

divine and earthly power were expressed in many ritual objects. One of the

ritual objects (made about 31st century BC and decorated on both

sides in low relief) was commemorated to the victory of King Narmer’s northern

army over his southern enemy. On one side of this carved stone palette, the king

(wearing the crown of the north) is shown behind his troops that are marching on

the enemy and defeating it. On the other side, Narmer (wearing the captured

crown of the south) is shown subjugating the leader of the south.

The notion that Narmer was wearing the enemy hat, while leading his

troops into the battle, is unreasonable, preposterous, and just "politically

correct". It was designed only to promote the unfounded notion that Upper Egypt

(and thus, central Africa) and not Mesopotamia was the primary stimulus of the

Egyptian progress. Those so-called scientists apparently do not understand the

meaning and relativity of the Greek word progress, which means ‘to move

forward’; however, moving forward in a circle, your finish may be at your start.

The notion that Narmer was wearing the enemy hat, while leading his

troops into the battle, is unreasonable, preposterous, and just "politically

correct". It was designed only to promote the unfounded notion that Upper Egypt

(and thus, central Africa) and not Mesopotamia was the primary stimulus of the

Egyptian progress. Those so-called scientists apparently do not understand the

meaning and relativity of the Greek word progress, which means ‘to move

forward’; however, moving forward in a circle, your finish may be at your start.

The logical beginning of the depicted event is on the top of the palette (on the

left), which was meant to be read from above. It is comprised of three registers

that lie below the heads of the cow goddess of love (Hathor) and the

king’s name. The heads of the cow goddess of love (the most respected divinity

of the nomadic people) imply that She guards the king from all sides. At the

first register, Narmer (wearing the crown of Lower Egypt) leads his warriors

(who have upraised standards) into the decisive battle. Hanging from the behind

of Narmer’s tunic is a ritual bull’s tail (each hair of which means a soldier),

which served to identify the king with the bull as a figure of power and the

symbol of the upper class. After the battle, the enemy is slaughtered and

unification of Lower and Upper Egypts is a fact. The unification is expressed on

the second register, where two felines (as the ancestral spirits of the

Egyptians roped by the bearded priests), with their elongated necks, form an

indented circle (unity). The indenture that was limited by the circle probably

served for mixing pigments. That is why this is the topside of the palette and

why it was meant to be viewed from above. In the lowest register, a bull (as a

manifestation of the power of the upper class and Narmer himself) subdues the

fallen upper class of the enemy.

The bottom of the palette is comprised of two registers that lie below the heads

of the cow goddess of love, which guard the king’s name (the box between the cow

heads). The scene, which depicted in the upper register, shows Narmer (already

wearing the captured, tall, conical crown of Upper Egypt), who threatens the

kneeling enemy leader (who is nearly the same size as Narmer) with a mace.

Narmer holds the enemy leader by the hair, thus symbolizing conquest and

domination. Over the head of the kneeling enemy is the falcon that symbolizes

the sky god of kingship (Horus). The falcon sits on the top of Narmer’s

boat that floats among the six (remember the Mesopotamian magical number, from

which 60 minutes and 360 degrees of a circle are derived) papyrus plants, which

represent Lower Egypt (from where and by what means Narmer came to the victory

battlefield). Behind Narmer is his servant, who holds Narmer’s sandals. Narmer

took off the sandals because he stands on the holy ground (as the Moslems take

off their shoes when entering their holy ground – a mosque, or like the Koreans,

when they enter a friend’s home). During the first dynasty of the Old Kingdom

servants were killed in order to accompany the dead king to his afterlife;

however, by the Middle Kingdom, the Egyptians considered that the paintings and

statues would be adequate substitutes. In the lower register, the partisans of

the enemy leader are fleeing from only seeing Narmer.

The important event that was

reflected on the palette depicts one of the historical stages that led to

unification of Egypt, and at the same time, it shows that the country had two

distinct parts (Upper Egypt in the south and Lower Egypt in the north). These

two distinct parts counter-balanced each other after each Dark Age, and did not

allow the Egyptians to work out a systematic ideology and to be completely one

nation under one God. Later, we will see why, but for now, the most impressive

evidence of the Mesopotamian influence may be seen in the earliest Egyptian

pyramids, called mastaba (from the Arabic word ‘a bench’ of mourning).

The kings of the early dynasties had tombs at Abydos and Saqqara (near the

capital of the Lower Egypt, Memphis) built in imitation of the Mesopotamian

ziggurats with shrines on top of them.

The important event that was

reflected on the palette depicts one of the historical stages that led to

unification of Egypt, and at the same time, it shows that the country had two

distinct parts (Upper Egypt in the south and Lower Egypt in the north). These

two distinct parts counter-balanced each other after each Dark Age, and did not

allow the Egyptians to work out a systematic ideology and to be completely one

nation under one God. Later, we will see why, but for now, the most impressive

evidence of the Mesopotamian influence may be seen in the earliest Egyptian

pyramids, called mastaba (from the Arabic word ‘a bench’ of mourning).

The kings of the early dynasties had tombs at Abydos and Saqqara (near the

capital of the Lower Egypt, Memphis) built in imitation of the Mesopotamian

ziggurats with shrines on top of them.

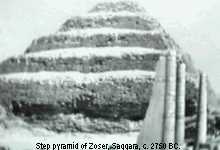

In the 3rd Dynasty the

architect and prime-minister Imhotep built for King Zoser, who ruled 2737-2717

BC, a burial complex at Saqqara, that included a stepped stone pyramid and a

group of shrines and related buildings. Designed to protect the remains of the

king, the great Step Pyramid is one of the oldest examples of monumental

architecture preserved; it also illustrates one of the phases toward the

development of the true pyramid. Apparently, Imhotep traveled through Sumer and

saw the ziggurats. After that, he constructed the pyramid at Saqqara, the shape

and size of which was nearly the same as those of ziggurats. He placed six

(remember the Sumerian magic number) mastabas of decreasing size on top of each

other (in the shape of pyramid) over a tomb some 30 meters underground. The

experimentation with the stepped pyramids followed and they were constructed

from different numbers of levels (mastabas). About two centuries later, the

three most famous pyramids were constructed at Giza, about 50 km north of

Saqqara.

In the 3rd Dynasty the

architect and prime-minister Imhotep built for King Zoser, who ruled 2737-2717

BC, a burial complex at Saqqara, that included a stepped stone pyramid and a

group of shrines and related buildings. Designed to protect the remains of the

king, the great Step Pyramid is one of the oldest examples of monumental

architecture preserved; it also illustrates one of the phases toward the

development of the true pyramid. Apparently, Imhotep traveled through Sumer and

saw the ziggurats. After that, he constructed the pyramid at Saqqara, the shape

and size of which was nearly the same as those of ziggurats. He placed six

(remember the Sumerian magic number) mastabas of decreasing size on top of each

other (in the shape of pyramid) over a tomb some 30 meters underground. The

experimentation with the stepped pyramids followed and they were constructed

from different numbers of levels (mastabas). About two centuries later, the

three most famous pyramids were constructed at Giza, about 50 km north of

Saqqara.

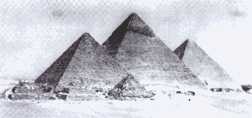

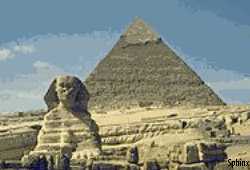

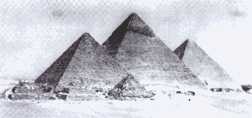

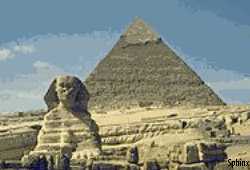

The architecture of the Old Kingdom (from the 3rd

through the 6th dynasties) can be described as monumental,

rectangular, and frontal. The native limestone and granite were used for the

construction of large-scale royal temples and royal and private tombs. The

pyramid complex at Giza (where the kings of the 4th Dynasty were

buried) illustrates the high intellectual level of Egyptian architects, who

could construct monuments that remain wonders of the world.

The architecture of the Old Kingdom (from the 3rd

through the 6th dynasties) can be described as monumental,

rectangular, and frontal. The native limestone and granite were used for the

construction of large-scale royal temples and royal and private tombs. The

pyramid complex at Giza (where the kings of the 4th Dynasty were

buried) illustrates the high intellectual level of Egyptian architects, who

could construct monuments that remain wonders of the world.

The Pyramid of Khufu was about 146-m high, 230-m along each side of its base,

and contained about 2.3 million rectangular blocks with an average weight of 2.5

tons each. The other two major pyramids at Giza were that of Khafre (Khufu’s

son) and that of Menkaure (Khafre’s son). They were built to preserve and

protect the bodies of the kings for eternity. Each pyramid had a valley temple,

a landing and staging area, and pyramid temple or cult chapel where religious

rites for the king’s spirit were performed. Around them, a royal cemetery grew

up, containing other upper class members’ mastaba tombs. For the most part these

tombs were constructed from rectangular blocks of stone over shafts that led to

a chamber containing the mummy and the offerings, but some tombs were cut into

the limestone plateau. From the evidence of tombs at Giza and Saqqara it appears

that the Egyptians built their tombs imitating their real houses, which they

arranged on the streets in the well-designed towns and cities. Because houses

and even palaces were built of unbaked mud bricks, they have not survived. The

temples and tombs, built of stone and constructed for eternity, provide most of

the information on the customs and living conditions of those Egyptians.

From the early figures of clay, bone, and ivory (in the

pre-dynastic period) Egyptian sculpture developed quickly. By the time of the 3rd

Dynasty, large statues of the rulers were made as resting-places for their

spirits. Egyptian sculpture is best described by the terms rectangular and

frontal. The rectangular block of stone was first cut out of a rock; then, the

design of the figure was drawn on the front and the two sides. The resulting

statue was meant to be seen mainly from the front; a timeless image meant to

convey the essence of the person depicted and not a momentary impression.

From the early figures of clay, bone, and ivory (in the

pre-dynastic period) Egyptian sculpture developed quickly. By the time of the 3rd

Dynasty, large statues of the rulers were made as resting-places for their

spirits. Egyptian sculpture is best described by the terms rectangular and

frontal. The rectangular block of stone was first cut out of a rock; then, the

design of the figure was drawn on the front and the two sides. The resulting

statue was meant to be seen mainly from the front; a timeless image meant to

convey the essence of the person depicted and not a momentary impression.

The Egyptian artists were not interested in showing the dynamic of a figure.

Figures were posed rather at rest (in static forms). From the beginning of the

dynastic period, the Egyptian sculptors understood human anatomy but idealized

it because they idealized their kings and gave the kings’ images a great deal of

heavenly dignity. A seated stone figure of Khafre (about 25th century

BC) embodies all the important royal qualities. The king sits on a throne

decorated with an emblem of the united lands, with his hands on his knees, head

erect, and eyes gazing into the far distance as if he contemplates over the

long-run interests of the Egyptians. A falcon of the sky god of kingship (Horus),

a son of a goddess of a king’s throne (Isis) behind him symbolizes his

divine right of kingship.

Several forms were developed to depict private persons. In addition to seated

and standing single figures, paired and group statues of the deceased with their

family members were also made. Sculpture was of stone, of wood, and (rarely) of

metal. Paint was applied to the surface and the eyes were inlaid in other

materials (such as rock crystal) to increase the lifelike appearance of

sculptures that depicted workers engaged in the crafts and food preparation.

These sculptures were meant to be included in the tomb as substitutes of the

actual relatives and servants. The images of relatives were meant to entertain

the royal spirit in his afterlife. The images of servants were meant to serve

the royal spirit in his next life. When the sculpture technique became so

advanced that the production of the image of the lower class individual became

cheaper than killing him, then, the images substituted the actual servants.

Thus, the necessity to kill the actual servants (after the death of their

master) fell away. Thus, the Old Kingdom canon that prescribed increasing

naturalism for decreasing social status was worked out.

Relief sculpture on the walls of temples depicted and immortalized the king in

relation to the Egyptians and their gods. In the chambered superstructures of

private tombs, the occupant was shown receiving offerings, enjoying, and

observing the various activities he had taken part in while living.

The method of representing the human figure in two dimensions, either carved in

relief or painted, was dictated by the desire to preserve the essence of what

was shown. Consequently, the typical depiction combines the head and lower body

as seen from the side, with the eye and upper torso as seen from the front. The

most understandable view of each part was used to create a complete image.

This rule (the Egyptian canon) was

applied to the images of the king and other members of the upper class, but the

images of the middle and lower class workers were not so rigidly enforced. When

some complicated actions had to be conveyed with the use of other points of view

of parts of the body, they were used; however, the face was rarely shown

frontally. Relief carving was usually painted to complete the lifelike effect,

and many details were added only in paint; however, purely painted decoration is

seldom found in remains of the Old Kingdom Age.

This rule (the Egyptian canon) was

applied to the images of the king and other members of the upper class, but the

images of the middle and lower class workers were not so rigidly enforced. When

some complicated actions had to be conveyed with the use of other points of view

of parts of the body, they were used; however, the face was rarely shown

frontally. Relief carving was usually painted to complete the lifelike effect,

and many details were added only in paint; however, purely painted decoration is

seldom found in remains of the Old Kingdom Age.

The Egyptian painters illustrated the various agricultural techniques and

methods of caring for flocks and herds, the trapping of wild animals, the

variety of food and culinary techniques, and the processes of building houses,

boats and other kinds of crafts. They arranged their illustrations on the walls

of tombs in registers (bands), which were meant to be read as continuous

narratives of the timeless occupations. The painters and sculptors (working in

relief) acted as a team, with different stages of the work assigned to different

members of the team.

Pottery of the pre-dynastic period (that was made with rich

decorations) was replaced by beautifully made, but undecorated wares, often with

burnished surfaces, in a variety of useful shapes. Pottery of the first

dynasties served all the purposes for which glass, china, metal, and plastic are

used today; consequently, it varied from vessels for eating and drinking to

large storage containers and brewer’s vats. Jewelry was made of gold and

semiprecious stones in forms incorporating plant and animal designs, because

agriculture was the main source of existence.

Pottery of the pre-dynastic period (that was made with rich

decorations) was replaced by beautifully made, but undecorated wares, often with

burnished surfaces, in a variety of useful shapes. Pottery of the first

dynasties served all the purposes for which glass, china, metal, and plastic are

used today; consequently, it varied from vessels for eating and drinking to

large storage containers and brewer’s vats. Jewelry was made of gold and

semiprecious stones in forms incorporating plant and animal designs, because

agriculture was the main source of existence.

Throughout the history of Egypt, the decorative arts were highly dependent on

the agricultural motifs. The number of illustrations in tombs give much

information about the design of chairs, beds, stools, and tables, which were,

generally, of simple design, incorporating plant forms and animal feet. The

columns of the temples and palaces were designed in the same plant-like forms.

From the age of the 6th Dynasty came the oldest surviving metal

statue, made of copper an image of Pepi I, who ruled 2395-2360 BC.

The Pyramid Texts are the mortuary texts that were carved inside the pyramids of

kings; they are the oldest preserved literature. The mortuary texts were

designed to ensure the dead ruler’s rightful place in the afterlife. These texts

incorporate hymns to the gods and daily offering rituals. Many autobiographical

inscriptions from private tombs recount the deceased’s participation in

historical events. Although no stories or ‘wisdom texts’ were preserved from the

Old Kingdom, some Middle Kingdom manuscripts may be copies of Old Kingdom

originals. Such a copy may be "The Instruction of the Vizier Ptahhotep"

composed of maxims illustrating basic virtues – such as moderation,

truthfulness, and kindness. This ‘wisdom text’ proclaimed that virtues should

govern human relations, and it described the ideal person as a just

administrator.

By the end of the 6th Dynasty’s rule, the clerical and local

bureaucracies began to take over the Egyptian central civil bureaucracy. The

priests and local governors gained in social status and personal wealth and

gradually undermined the divine and absolute authority of the king. The power of

the central bureaucracy had been weakened, and henceforth, the local bureaucrats

chose to be buried in own provinces rather than near the royal burial places.

The extreme expenditure of human

and material resources on the army and on pyramids by the central bureaucracy

led to demoralization and corruption of the central bureaucrats, and the 6th

Dynasty declined and died out. The collapse of the central bureaucracy led to

the civil war when rival families competed for the throne and had no time and

money to look around for the nomadic tribes. The irrigation system required

constant maintenance, but nobody had taken responsibility for it. The lower

class Egyptians were starved to death and the country was depopulated.

The extreme expenditure of human

and material resources on the army and on pyramids by the central bureaucracy

led to demoralization and corruption of the central bureaucrats, and the 6th

Dynasty declined and died out. The collapse of the central bureaucracy led to

the civil war when rival families competed for the throne and had no time and

money to look around for the nomadic tribes. The irrigation system required

constant maintenance, but nobody had taken responsibility for it. The lower

class Egyptians were starved to death and the country was depopulated.

Following the breakdown of the Old Kingdom, private individuals appropriated the

Pyramid Texts and supplemented them with new incantations. Since then, these

texts were painted on the coffins of commoners, who also had their tombs

inscribed with autobiographical texts, which often recounted their exploits

during this time of political unrest. To this 1st Dark Age (c.

2181-2040 BC) are attributed various laments over the chaotic state of affairs.

One of these, "The Dialogue of a Man with his Soul", is a debate of commoners on

a theme of suicide. The earliest example of the songs sung by harpists at the

funerary banquets of the upper class, advises "Eat, drink, and be merry, before

it’s too late!" Moreover, an anonymous Egyptian poet of that time thus reflected

the situation:

The wrongdoer is everywhere….

Plunderers are everywhere….

Nile is in flood, yet none ploughs for him….

Thus, Egypt became an easy prey for the nomads, who would be the Egyptian new

and more organized upper class.

2) Middle Kingdom

The 1st Transitional period (the 7th through the 10th

Dynasties) was a time of anarchy and civil wars. Artistic traditions of the Old

Kingdom survived only when the strong rulers emerged in Thebes, the capital city

of Upper Egypt. The rulers of Thebes, who employed the Nubian tribesmen as their

mercenaries, reunited the country and made healthy conditions for the

middle-class activity. Under Mentuhotep II of the 11th Dynasty (who

ruled Egypt from 2040 to 2010 BC and united it in the Middle Kingdom period),

the Egyptians artists and artisans created a new style of the mortuary

monuments. The pyramid complexes of the Old Kingdom were their inspiration. On

the West Bank of the Nile, at Thebes, the Egyptians constructed a valley temple

connected by a causeway to a temple, nestled in the rocky hillside. The walls

were decorated with reliefs of the king in the company of the gods.

The ideology of the Egyptians had the dominating influence in the development of

their culture (as in every other culture), although it did not develop into a

national religion, in the sense of a unified theological system. The unification

of the Egyptian ideology was not completed because of the shifts of central

power from the descendants of the different nomadic tribes. The Egyptian upper

class has been comprised from the Semitic Dynasties that ruled from Memphis,

then, from the Nubian Dynasties that ruled from Thebes. The Egyptians were ruled

by the Libyan Dynasties from Sais, Tanis, and Bubastis, by the Aryan Dynasties

from Persepolis, Alexandria, Rome, and Constantinople, by the Semitic Arabs

again, and so forth. Thus, the Egyptian system of faith had not been

systematized. Although the efforts in this direction were made, but they were

weak and sporadic, leaving only an unorganized collection of ancient myths,

nature worship, and innumerable deities. In the most influential and famous of

these myths, a divine hierarchy is developed and the creation of the earth is

explained.

According to the earlier Egyptian accounts of creation, at first, only the ocean

existed. Then, the sun (Ra) came out of an egg (a flower – lotus, in some

versions) that appeared on the surface of the water. The sun and water brought

forth two sons, the air (Shu) and earth (Geb), and two daughters,

the clouds (Tefnut) and sky (Nut). The sun ruled over all. The

earth and the sky later had two sons, Set and Osiris, and two daughters, Isis

and Nephthys. The younger brother (Osiris) succeeded his father (Ra) as king of

the world because his sister-wife (Isis) helped him. However, the elder brother

(Set) hated his younger brother and killed him. (You can see from where Moses

took his scenario of Cain killing Abel.) Isis then embalmed her husband’s body

with the help of Anubis, who thus became the god of embalming. The powerful

charms of Isis resurrected Osiris, who became king of the netherworld, the land

of the dead. The son of Osiris and Isis, Horus, who later defeated Set in a

great battle, became the king of the world.

From this myth of creation came the conception of the Ennead, a group of nine

divinities, and the Trinity, consisting of a divine father, mother, and son.

Every local temple in Egypt possessed its own Ennead and Trinity. Most of the

Egyptians of the Old Kingdom had known the Ennead that included the sun (Ra) and

his children and grandchildren. In the 12th Dynasty (the second after

the 1st Dark Age) the Nubian sun god (Amon) superseded the

Semitic sun god (Ra), and then, in the 18th Dynasty (the first

after the 2nd Dark Age), the supreme god became the new Nubian sun

god (Aton).

From Egyptian, Amon means ‘hiding’; it also spelled as Ammon, Amen, or

Amun. Originally, Amon was the sun god of the Nubian nomads; his dominant

feature was his reproductive forces. Thus, Amon had been pictured as a ram.

Later, the Egyptian upper class had civilized him and pictured him as a human.

Amon, his wife, Mut (from Egyptian means ‘mother’), and his son, the moon god

Khon (from Egyptian means ‘to traverse the sky’), formed the Trinity of Thebes.

Later, the Egyptian upper class made an attempt of unification of these deities.

The Egyptian priests identified the sun god (Amon) of Thebes with the sun god

(Ra) of Heliopolis, and he became known as Amon-Ra, "the father of the gods, the

fashioner of men, the creator of cattle, the Lord of all being". For awhile,

this semi-universal sun god became the national god of the Egyptians, but the

other deities were worshiped too. The power of the high priest of the sun god

(Amon-Ra) rivaled that of the power of the king, provoking political problems

similar to modern church-state rivalry, and finally led to the 2nd

Egyptian Dark Age. The biggest temple ever built for Amon-Ra was at Karnak, near

Thebes. Later, Amon was worshiped in the ancient Greek colonies of Cyrene, where

he was identified with Zeus. Still later, in Rome, Amon was associated with

Jupiter.

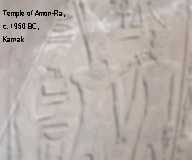

Hieroglyphs at the temple of Amon-Ra, Karnak, glorify King Sesostris I (Senusret

I), the second king of the 12th Dynasty, who ruled the Egyptians

during the years 1971-1928 BC. He was a son of Amonemhet I and the father of

Amonemhet II. Sesostris ruled as co-regent with his father during the years

1971-1962, and became a sole ruler from 1962 BC. He led the Egyptian army

against the Nubians and the Libyans. Under his command, the Egyptian upper class

completed conquest of Nubia and penetrated into Cush. During his reign, the

Egyptian middle and lower classes built Karnak at Thebes and Sesostris' own

pyramid at Lisht. Sesostris also made his son co-regent in 1929 BC.

At this low relief at Karnak, the bearded Amonemhet I is wearing

the conical hat of the Upper Egypt and conducts his son, Sesostris I (a prince

of the Lower Egypt who is wearing the Lower Egyptian hat) to their common LORD

(Amon-Ra). The latter is waiting of this political novice with his erected penis

and, apparently, will soon "know" him in the biblical sense. Thus, Amon-Ra will

teach the novice what political power is all about. Thus, the upper class notion

of political power converges with the notion of the political power of the lower

class prisoners-homosexuals, who think that having somebody sexually makes them

the top-dogs of the prison, and thus, they would dominate and take into

possession those, whom they would copulate. That is why love can converge

with hate. That is why love (Platonic love) can be expressed in

the most elevating and poetic words. That is why love (jealous love) can

be expressed in the most demeaning and dirty four-letter words. And the writers

of the Old and New Testaments thus interpreted this notion:

At this low relief at Karnak, the bearded Amonemhet I is wearing

the conical hat of the Upper Egypt and conducts his son, Sesostris I (a prince

of the Lower Egypt who is wearing the Lower Egyptian hat) to their common LORD

(Amon-Ra). The latter is waiting of this political novice with his erected penis

and, apparently, will soon "know" him in the biblical sense. Thus, Amon-Ra will

teach the novice what political power is all about. Thus, the upper class notion

of political power converges with the notion of the political power of the lower

class prisoners-homosexuals, who think that having somebody sexually makes them

the top-dogs of the prison, and thus, they would dominate and take into

possession those, whom they would copulate. That is why love can converge

with hate. That is why love (Platonic love) can be expressed in

the most elevating and poetic words. That is why love (jealous love) can

be expressed in the most demeaning and dirty four-letter words. And the writers

of the Old and New Testaments thus interpreted this notion:

"I delight greatly in the LORD; my

soul rejoices in my God. For he has clothed me with garments of salvation and

arrayed me in a robe of righteousness, as a bridegroom adorns his head like a

priest, and as a bride adorns herself with her jewels. For as the soil makes the

sprout come up and a garden causes seeds to grow, so the Sovereign LORD will

make righteousness and praise spring up before all nations". (Isaiah 61:10) "As

a young man marries a maiden, so will your sons marry you; as a bridegroom

rejoices over his bride, so will your God rejoice over you". (Isaiah 62:5)

"I delight greatly in the LORD; my

soul rejoices in my God. For he has clothed me with garments of salvation and

arrayed me in a robe of righteousness, as a bridegroom adorns his head like a

priest, and as a bride adorns herself with her jewels. For as the soil makes the

sprout come up and a garden causes seeds to grow, so the Sovereign LORD will

make righteousness and praise spring up before all nations". (Isaiah 61:10) "As

a young man marries a maiden, so will your sons marry you; as a bridegroom

rejoices over his bride, so will your God rejoice over you". (Isaiah 62:5)

"They said to him, 'John's disciples often fast and pray, and so do the

disciples of the Pharisees, but yours go on eating and drinking'. Jesus

answered, 'Can you make the guests of the bridegroom fast while he is with them?

But the time will come, when the bridegroom will be taken away from them [and

become the bride himself, VS]; in those days they will fast'." (Luke 5:34)

If you take into consideration the columns of the temple of Ramses II, the stone

with the laws of Hammurabi, and the Washington Monument in the scenery with the

Capitol Dome, then you will understand what the primary source of political

power is.

Some consistency in worship to the

sun god might be traced from the worship to Ra, chief of cosmic deities, from

whom early Semitic-Egyptian kings claimed descent. Beginning with the 1st

Dark Age, Ra worship acquired the status of a state religion. During the

following Nubian-Egyptian dynasties, the sun god Ra was gradually fused with the

sun god Amon, thus becoming the supreme god Amon-Ra at Thebes. After the 2nd

Dark Age, during the 18th Dynasty, the king Amonhotep III renamed the

sun god Aton, an ancient Nubian term for the sun as a physical source of

daylight. Amonhotep’s son and successor, Amonhotep IV, reformed the Egyptian

ideology by proclaiming Aton the true and only god. Thus, Amonhotep IV adopted a

monotheistic ideology. From Greek, mono means ‘one’ and theo means

‘god’. The only god became the sun god Aton. Amonhotep changed his own name to

Ikhnaton, meaning, ‘Aton is satisfied’. This first great monotheist was so

orthodox and iconoclastic that he ordered to delete the plural word gods from

all monuments, and he relentlessly persecuted the priests of Amon-Ra. He moved

Egypt’s capital down the Nile from Thebes to Amarna, in Middle Egypt. Ikhnaton’s

ideology failed to become the national ideology because it was not systematized

– the different natural feminine powers were not linked to the masculine power

of the sun. Therefore, the priests of the other powers (gods) were resentful to

the monotheistic ideology.

Some consistency in worship to the

sun god might be traced from the worship to Ra, chief of cosmic deities, from

whom early Semitic-Egyptian kings claimed descent. Beginning with the 1st

Dark Age, Ra worship acquired the status of a state religion. During the

following Nubian-Egyptian dynasties, the sun god Ra was gradually fused with the

sun god Amon, thus becoming the supreme god Amon-Ra at Thebes. After the 2nd

Dark Age, during the 18th Dynasty, the king Amonhotep III renamed the

sun god Aton, an ancient Nubian term for the sun as a physical source of

daylight. Amonhotep’s son and successor, Amonhotep IV, reformed the Egyptian

ideology by proclaiming Aton the true and only god. Thus, Amonhotep IV adopted a

monotheistic ideology. From Greek, mono means ‘one’ and theo means

‘god’. The only god became the sun god Aton. Amonhotep changed his own name to

Ikhnaton, meaning, ‘Aton is satisfied’. This first great monotheist was so

orthodox and iconoclastic that he ordered to delete the plural word gods from

all monuments, and he relentlessly persecuted the priests of Amon-Ra. He moved

Egypt’s capital down the Nile from Thebes to Amarna, in Middle Egypt. Ikhnaton’s

ideology failed to become the national ideology because it was not systematized

– the different natural feminine powers were not linked to the masculine power

of the sun. Therefore, the priests of the other powers (gods) were resentful to

the monotheistic ideology.

The ideology became the main organizing force in the agricultural society

because it provided satisfactory explanations for the powers of nature; it

helped to ease the anxiety of death, and justified the traditional rules of

morality. Every society that wishes-to-survive must allocate its basic

resources in the way of matching the social roles with rewards. However, the

leaders of a society usually allocate the surplus resources in the

way that the lion’s share of them goes to the upper class. To justify such

unequal distribution the leaders need a moral ideology. Thus, the moral

ideology of the upper class is born, and thus, it becomes the basic part of the

society’s culture. All following laws are considered as the commandments of the

gods. Religion united people in the common enterprises that were needed for

their collective survival, such as conquering territories that are more fertile

or construction and maintenance of the irrigation systems. Religion became the

special inventions of urban culture. It became organizing instruments in the

hands of the ideologists, who shaped the upper class. With this instrument they

could discipline, drill, and handle the large masses of people as units in their

destructive assaults of "alien" peoples, their extermination, seizures, and

enslavement.

The first monotheistic ideology was going in the right direction, but it failed

for lack of knowledge. Consequently, it did not survive the death of its

originator, although it exerted a great influence on the culture of that and

following times, and gave the stimulus for Moses’ monotheistic ideology.

Meanwhile, Egypt returned to the ancient and labyrinthine ideology with many

powers to look for.

The origin of the local deities is

obscure; some of them were taken from the nomadic predecessors of the incoming

upper classes, and some were originally the animal gods of the prehistoric

Nile-region. Gradually, they were all fused into a complicated religious

structure, although comparatively few local divinities became important

throughout Egypt. In addition to those already named, the important divinities

included the Semitic gods Thoth, Ptah, Khnemu, and Hapi, and the goddesses

Hathor, Mut, Neit, and Sekhet. Their importance increased with the political

ascendancy of the localities where they were worshiped. For example, a Trinity

of the father Ptah, the mother Sekhet, and the son Imhotep headed the Ennead of

Memphis. Ancient inscriptions describe Ptah as "creator of the earth, father of

the gods and all the being of this earth, father of beginnings". He was regarded

as the patron of metalworkers and artisans and as a mighty healer. He is usually

represented as a mummy bearing the symbols of life, power, and stability. The

main center of his worship was in Memphis.

The origin of the local deities is

obscure; some of them were taken from the nomadic predecessors of the incoming

upper classes, and some were originally the animal gods of the prehistoric

Nile-region. Gradually, they were all fused into a complicated religious

structure, although comparatively few local divinities became important

throughout Egypt. In addition to those already named, the important divinities

included the Semitic gods Thoth, Ptah, Khnemu, and Hapi, and the goddesses

Hathor, Mut, Neit, and Sekhet. Their importance increased with the political

ascendancy of the localities where they were worshiped. For example, a Trinity

of the father Ptah, the mother Sekhet, and the son Imhotep headed the Ennead of

Memphis. Ancient inscriptions describe Ptah as "creator of the earth, father of

the gods and all the being of this earth, father of beginnings". He was regarded

as the patron of metalworkers and artisans and as a mighty healer. He is usually

represented as a mummy bearing the symbols of life, power, and stability. The

main center of his worship was in Memphis.

Consequently, during the Semitic-Egyptian dynasties of Memphis, Ptah became one

of the greatest gods in Egypt. Similarly, when the Nubian-Egyptian dynasties of

Thebes ruled Egypt, the Trinity of the father Amon, the mother Mut, and the son

Khon (that headed the Ennead of Thebes) was given the most importance by the

ruling bureaucracy. As the religion became more involved in the affairs of the

State, the deities were sometimes confused with human beings that had been

glorified after death. Thus, Imhotep, who was originally the chief minister of

King Zoser of the 3rd Dynasty, was later regarded as a demigod.

During the 5th Dynasty, the kings began to claim divine ancestry and,

from that time on, were worshiped as sons of the sun god. Minor powers were also

given places in local divine hierarchies.

The Egyptian gods were represented with human torsos and human or animal heads.

Sometimes the animal or bird expressed the characteristics of the god. The sun

god (Ra), for example, had the head of a hawk, and the hawk was sacred to him

because of its swift flight across the sky. Hathor, the goddess of love and

laughter, was pictured as cow-headed, and a cow was sacred to her. Anubis was

given the head of a jackal because these animals ravaged the desert graves in

ancient times. Mut was pictured as vulture-headed, Thoth was ibis-headed, and

Ptah was given a human head, although he was occasionally represented as a bull,

called Apis. Because of the gods to which they were attached, the sacred animals

were venerated, but they were not worshiped until the 26th Dynasty

(after the Assyrian domination). The gods were also represented by symbols, such

as the sun disk and hawk wings that were worn on the headdress of the king.

Burying the dead was of the primary

concern of the Egyptians, and thus, their funerary rituals and equipment

eventually became the most elaborate the world has ever known. The Egyptians

believed that the vital life force was composed of several psychical elements,

of which the most important was the soul (Ka). The soul, a duplicate of

the body, accompanied the body throughout life and, after death, departed from

the body to take its place in the land of the dead. However, the soul could not

exist without the body; therefore, every effort had to be made to preserve the

corpse. Bodies were embalmed and mummified according to a traditional method

(that was supposedly created by Isis, who mummified her husband Osiris).

Moreover, wood or stone replicas of the body were put into the tomb, just in

case if the mummy would be somehow destroyed. Than more statue-duplicates the

individual had in his tomb, the more chances he had of resurrection.

Consequently, exceedingly elaborate protective system of the tombs was designed

to protect the corpses and their afterlife equipment from all kind of natural

and social disasters.

Burying the dead was of the primary

concern of the Egyptians, and thus, their funerary rituals and equipment

eventually became the most elaborate the world has ever known. The Egyptians

believed that the vital life force was composed of several psychical elements,

of which the most important was the soul (Ka). The soul, a duplicate of

the body, accompanied the body throughout life and, after death, departed from

the body to take its place in the land of the dead. However, the soul could not

exist without the body; therefore, every effort had to be made to preserve the

corpse. Bodies were embalmed and mummified according to a traditional method

(that was supposedly created by Isis, who mummified her husband Osiris).

Moreover, wood or stone replicas of the body were put into the tomb, just in

case if the mummy would be somehow destroyed. Than more statue-duplicates the

individual had in his tomb, the more chances he had of resurrection.

Consequently, exceedingly elaborate protective system of the tombs was designed

to protect the corpses and their afterlife equipment from all kind of natural

and social disasters.

The soul of the dead supposedly is

beset by innumerable dangers while leaving the tomb; therefore, the tombs were

furnished with a copy of the Book of the Dead. In part, this book is a guide to

the world of the dead, which was designed to overcome these dangers with some

charms. After arriving in the land of the dead, the soul was judged by Osiris,

the ruler of the dead, who had 42 assistants. The Book of the Dead also contains

instructions for proper conduct before these judges. If the judges decided that

the deceased had been a sinner, his soul would be condemned to hunger and thirst

or would be torn to pieces by horrible executioners. If the decision was

favorable, then, the soul went to a kind of paradise (the heavenly realm of the

fields of Yaru, where grain grew nearly four meters high, milky rivers with

honey banks were flowing, and existence was an extremely pleasurable version of

life on this earth).

The soul of the dead supposedly is

beset by innumerable dangers while leaving the tomb; therefore, the tombs were

furnished with a copy of the Book of the Dead. In part, this book is a guide to

the world of the dead, which was designed to overcome these dangers with some

charms. After arriving in the land of the dead, the soul was judged by Osiris,

the ruler of the dead, who had 42 assistants. The Book of the Dead also contains

instructions for proper conduct before these judges. If the judges decided that

the deceased had been a sinner, his soul would be condemned to hunger and thirst

or would be torn to pieces by horrible executioners. If the decision was

favorable, then, the soul went to a kind of paradise (the heavenly realm of the

fields of Yaru, where grain grew nearly four meters high, milky rivers with

honey banks were flowing, and existence was an extremely pleasurable version of

life on this earth).

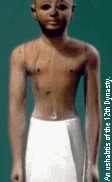

Consequently, all the necessities

for this happy afterlife existence (from furniture to literature) were put into

the tombs. As the reciprocal payment for the happy afterlife and his benevolent

protection, Osiris required the souls to perform tasks for him, such as working

in his grain fields. However, not breaking the reciprocity, the duty of manual

labor could be evaded by placing small statuettes (called ushabtis) into

the tomb to serve as substitutes for the deceased.

Consequently, all the necessities

for this happy afterlife existence (from furniture to literature) were put into

the tombs. As the reciprocal payment for the happy afterlife and his benevolent

protection, Osiris required the souls to perform tasks for him, such as working

in his grain fields. However, not breaking the reciprocity, the duty of manual

labor could be evaded by placing small statuettes (called ushabtis) into

the tomb to serve as substitutes for the deceased.

In the Middle Kingdom period, this theory was changed for a more realistic one,

because the supreme god became Amon-Ra, and the center of the new cult switched

to Thebes. There are a few preserved examples of the Middle Kingdom architecture

(the 11th and 12th Dynasties). A small building of

Sesostris I of the 12th Dynasty has been recovered from one of the

later pylons of the Karnak Temple, for which its blocks were reused as filling

material. This small chapel, actually a station for the procession of a sacred

boat, may be used to typify the style of the time. Essentially rectangular in

design and constructed on the post-lintel (two vertical posts and a horizontal

crossbeam) system, this small building has proportions that meant to express its

timeless character. The piers are decorated in fine raised relief with images of

the king and the gods.

The famines and civil wars were not forgotten and the Egyptian painters and

sculptors had attempted to express those feelings and thoughts in their

paintings and sculptures. Thus, the artifacts of the Middle Kingdom Age seem to

be more realistic than those, which came from the previous Age. The early work

of the Middle Kingdom Age directly imitates the Old Kingdom examples in an

attempt to restore old traditions and techniques that were lost in the Dark Age.

It takes time for the new generations of artists to reinvent the forgotten

techniques of their trade. However, the sculpture of the second half of the 12th

Dynasty exhibits an interest in reality. Portraits of rulers such as Amonemhet

III and Sesostris III, who ruled 1878-1843 BC, are different from those of the

Old Kingdom rulers; these images of the king are only slightly idealized.

These figures were not brought to the godlike images of the earlier Age because

relations between the social classes were changed and the memories of betrayal

popped up and burst into skepticism. Thus, the ideology of skepticism began to

show its ugly face. The new artists reflected in their portraits and sculptures

the new kings’ care and concern of the bureaucratic office; however, the bone

structure, indicated beneath tight surfaces that imitated skin, produced the

predator-type of realism that was not regular before. At all times, statues of

the members of the upper class tended to imitate the royal style; and the

statues of the upper class individual of the 12th Dynasty show that

kind of realism.

The tombs of the upper class individuals continued to be placed in their own

centers of influence rather than at the royal cemetery near the capital city

(some kind of the Arlington cemetery). Although many of these tombs were

decorated in relief carving like the Aswan tombs in the south, the tombs at Beni

Hassan in Middle Egypt were often decorated only with painting. Those that were

preserved show that the provincial artisans were trying to adhere to the

standards of royal workshops. Some new types and depictions appear, but the old

standards served as a guide to the subjects and arrangements. Painting is also

illustrated by the decoration of the rectangular wooden coffins typical of this

period.

In the Middle Kingdom, the decorative arts were abundantly produced; jewelry was

made of precious metals inlaid with colored stone. The art of faience

(tin-oxide-glazed earthenware) achieved a new importance for the manufacture of

amulets and small figures, such as the blue-glazed hippopotamuses decorated with

painted water plants.

Besides already mentioned Coffin Texts, the Middle Kingdom period left numerous

texts of ritual hymns to a king and various deities, including a long hymn to

the Nile. Private autobiographies containing historical information continued to

be inscribed, and rulers began setting up Stella (stone slabs) on which their

important deeds were recorded. From the 1st Dark Age and the Middle

Kingdom periods came some stories and instructional texts. The latter were

written in the name of a reigning king, who tried to explain his son and

successor how his specific political decisions might be bad, and thus influence

his future leadership.

"The Satire on Trades" stresses the bad aspects of all possible

occupations except the profession of the scribe. "The Story of Sinuhe"

narrates of a high-ranking bureaucrat, who fled to Syria and became a rich and

important man there at the death of King Amonemhet I. Amonemhet was the first of

the 12th Dynasty, the last dynasty before the 2nd Dark

Age. Amonemhet tried to limit the power of the local and clerical bureaucracies

through reorganizing the central government and moving the capital to Faiyum,

but his son, Sesostris I, returned it at Thebes. "The Story of the

Shipwrecked Sailor" recounts a marvelous encounter of the Sailor with a

giant snake on a luxuriant island. "The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant"

narrates of a man who was so eloquent pleading for the return of his stolen

donkeys that the bureaucrats kept him in protective custody for a while, in

order to enjoy his orations. "The Story of King Khufu and the Magicians"

is the earliest preserved medical and mathematical papyri of the Middle Kingdom

period.

3) New Kingdom

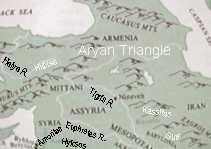

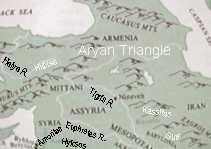

The 2nd Transitional period (13th through 17th

Dynasties) was a time of another disintegration of Egypt and anarchy among the

ruling bureaucracy. The period of the 13th Dynasty was a speedy

procession of 50 or more rulers in about 120 years. Upper Egypt broke away from

the central bureaucracy. The Hyksos, the Semitic nomadic tribes of Syria and

Lebanon, took the rotten Egyptian bureaucracy by surprise and established the 17th

Dynasty in Egypt. The Hyksos sacked the land and set themselves up as the upper

class and rulers of Lower Egypt. This had a lasting impact on the land, because

the Hyksos brought to Egypt new technology (new types of chariots and body

armor) and a new and broader view on the Mediterranean world. The new

bureaucracy dominated Lower Egypt about a century; however, for the lack of

knowledge about native conditions, it became too dependent on the clerical

bureaucracy, and soon, degenerated. The reunification of Egypt came from Upper

Egypt, and Thebes was reestablished as its capital city. Most of the

Hykso-Egyptians had been expelled by the Nubian-Egyptians, but a small portion

of them, which collaborated with the newly established upper class, became the

middle-class of merchants and artisans. Later, when the Libyan nomads would

establish a new upper class and the Nubian-Egyptian would be transferred into

the middle-class, the Hykso-Egyptians would probably become the lower class of

the forced laborers. However, fearing to become the lower class, the twelve

extended families of them would again prefer to become the nomads under the

leadership of Moses, who preached the Judaic ideology.

The New Kingdom, beginning with the

18th Dynasty of the Nubian descent came to power, wealth, and

influence, which were materialized through extensive foreign trade and

territorial expansion. The kings of the 18th through 20th

Dynasties were great empire builders and they were generous to the religious

architects. The most important deity in Egypt became the local god Amon. Almost

every ruler in the New Kingdom had added something to the cult center of Amon,

at Karnak. The result is one of the most impressive temple complexes in the

human history. Pylon gateways, colonnaded courts, and columnar halls with

obelisks and statues created an impressive display of the power of the king and

the clerical and state bureaucracies.

The New Kingdom, beginning with the

18th Dynasty of the Nubian descent came to power, wealth, and

influence, which were materialized through extensive foreign trade and

territorial expansion. The kings of the 18th through 20th

Dynasties were great empire builders and they were generous to the religious

architects. The most important deity in Egypt became the local god Amon. Almost

every ruler in the New Kingdom had added something to the cult center of Amon,

at Karnak. The result is one of the most impressive temple complexes in the

human history. Pylon gateways, colonnaded courts, and columnar halls with

obelisks and statues created an impressive display of the power of the king and

the clerical and state bureaucracies.

On the West Bank of the Nile, near the royal cemetery of Thebes, temples for the

gods and the funerary cults of kings were built. During the New Kingdom, the

bodies of the rulers were buried in rock-cut tombs in the dry Valley of the

Kings, with the mortuary temples at some distance outside the valley. One of the

first and most unusual was the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut, built about

1478 BC under the management of the royal architect, Senemut. Situated against

the Nile cliffs, next to the 11th Dynasty temple of Mentuhotep II,

and apparently inspired by it, the temple is a vast terraced structure with

numerous shrines to the gods and reliefs that depict the queen’s

accomplishments. Other rulers did not follow the precedent and continued to

build their mortuary temples at the edge of the cultivated land, away from the

cliff-side. The rock-cut tombs were deepened into the cliff-sides of the Valley

of the Kings in an effort to conceal the resting-places of the royal mummies.

The long descending passageways, stairs, and chambers were decorated in relief

and painting with scenes from religious texts intended to protect and aid the

spirit in the next life.

The Book of the Dead, the mortuary texts of the Middle Kingdom period that were

written on papyrus, were meant to be included in the tombs of the New Kingdom

period. Among the most famous hymns from this period are those from the reign of

Ikhnaton dedicated to the sun god as the sole god. King Kamose, who ruled about

1576-1570 BC, at the end of the 2nd Dark Age (1786-1570 BC), recorded

the early stages of driving the Hyksos-Egyptians out of Egypt (1600 BC). After

the early New Kingdom, the number of such royal historical inscriptions

increased greatly, while private autobiographical texts gave way to the

ideological texts.

Thutmose III boasted his various wars in Syria on his so-called the Poetical

Stella and on the walls of the temple at Karnak. Both records describe how the

king called in his advisors to apprise the difficult situation. The advisors

advised to try the easy way, but he told them that he is not afraid and will

dare the more dangerous route. Finally, the king’s course succeeded. The

extensive records of the Late New Kingdom rulers were preserved. Ramses II and

Ramses III of the 19th Dynasty left poetic accounts and chronicles of

their deeds and military exploits, such as the Battle of Kadesh, where Ramses II

"succeeded" against the Aryan Hittites. These instructive texts were directed at

low-rank bureaucrats, trying to explain them why acting on the assumption that

right thinking and just action (which supposedly would automatically lead to

worldly success) is not enough. Instead, the texts promote the idea that a

prolonged contemplation and endurance would suffice. Among the stories that were

preserve and are worthy to mention is "The Destruction of Mankind", in

which humanity is spared from annihilation by getting the goddess Hathor drunk

on blood-colored beer. "The Tale of the Two Brothers" is a story of a

good younger brother betrayed by his suspicious elder brother.

Under Ramses II, the Egyptians cut

into the mountainside and created the gigantic temple of Abu Simbel in Nubia to

the south, with four colossal figures of the king in front. This temple was

saved from immersion beneath the waters of the new Aswan High Dam. In 1968, the

Egyptians cut out facade and halls of the temple of the mountain and moved it to

a higher site.

Under Ramses II, the Egyptians cut

into the mountainside and created the gigantic temple of Abu Simbel in Nubia to

the south, with four colossal figures of the king in front. This temple was

saved from immersion beneath the waters of the new Aswan High Dam. In 1968, the

Egyptians cut out facade and halls of the temple of the mountain and moved it to

a higher site.

Domestic and palace architecture was built of perishable mud bricks, because the

houses and palaces were meant to serve for the mortals. However, remains that

were preserved convey an idea of well-designed multi-roomed palaces with painted

floors, walls, and ceilings. Houses for the upper classes were arranged like

small estates, with residential and service buildings in an enclosed compound.

Examples of the middle and lower classes workers’ dwellings were also found.

They were clustered together in villages, very much like those of modern Egypt.

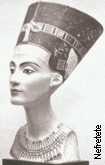

The

art of sculpture in the New Kingdom reached a new height. The extreme idealism

of the absolute monarchy in the Old Kingdom and the bitter realism of the

somewhat constitutional monarchy in the Middle Kingdom were replaced with a

polite style of the constitutional monarchy that combined beautification with

attention to delicate detail (the Egyptian Baroque). Begun in the reigns of

Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, this style reached maturity in the time of

Amonhotep III. Portraits of the rulers and other members of the upper class of

this period are saturated with grace and sensuality.

The

art of sculpture in the New Kingdom reached a new height. The extreme idealism

of the absolute monarchy in the Old Kingdom and the bitter realism of the

somewhat constitutional monarchy in the Middle Kingdom were replaced with a

polite style of the constitutional monarchy that combined beautification with

attention to delicate detail (the Egyptian Baroque). Begun in the reigns of

Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, this style reached maturity in the time of

Amonhotep III. Portraits of the rulers and other members of the upper class of

this period are saturated with grace and sensuality.

The art of the time of Ikhnaton (son of Amonhotep III) reflects the ideological

reformation that Ikhnaton tried to promote. Ikhnaton worshiped the sun god (Aton)

and he insisted that the artists should reflect the new direction. Early in his

reign, a realism that verged upon caricature was used. However, this realism

developed into a beautifying style, which tend to eliminate all rigid and sharp

characteristics of a personality. This style was embodied in the painted

limestone head of Nefertiti, Ikhnaton’s wife (c. 1365 BC).

In the New Kingdom relief carving

was generally used for the decoration of tombs and temples, but at Thebes, wall

painting came to dominate the decoration of private tombs. The medium of

painting made possible a wider range of expression than sculpture, allowing the

artist to create colorful tableaus of life on the Nile. Funerary rites are

illustrated from the procession to the tomb to the final prayers for the spirit.

In the New Kingdom relief carving

was generally used for the decoration of tombs and temples, but at Thebes, wall

painting came to dominate the decoration of private tombs. The medium of

painting made possible a wider range of expression than sculpture, allowing the

artist to create colorful tableaus of life on the Nile. Funerary rites are

illustrated from the procession to the tomb to the final prayers for the spirit.

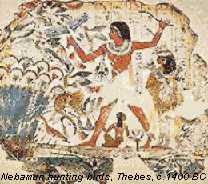

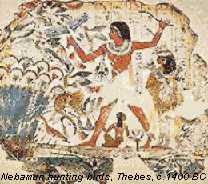

One of the standard elements of the Old Kingdom canon in the Theban tomb

paintings is a representation of a deceased hunting and fishing in the papyrus

marshes. His joyful pastimes symbolized his triumph in afterlife over the malign

dark forces of this world. The painters showed the local bureaucrats inspecting

the exotic merchandise brought to Egypt from all parts of the known world. The

crafts of the royal workshops are depicted in meticulous detail, illustrating

the production of all kinds of articles, from massive sculptures to fine

jewelry.

The

decorative arts of the New Kingdom are equal to the sculpture and painting in

their high level of accomplishment. The best example of them is in the funerary

items from the tomb of Tutankhamen, in which rich materials (alabaster, ebony,

gold, ivory, and semiprecious stones) were combined in objects of high artistry.

Ordinary objects for the use of the king and other members of the upper class

were exquisitely designed and made with great care. Even the pottery of that

time partakes in this desire for decorations, which were colorfully painted on

the pottery surfaces employing mostly floral motifs. From the evidence of tomb

paintings and the decorative arts follows that the Egyptians of that time had

optimistic outlook on the life in this world.

The

decorative arts of the New Kingdom are equal to the sculpture and painting in

their high level of accomplishment. The best example of them is in the funerary

items from the tomb of Tutankhamen, in which rich materials (alabaster, ebony,

gold, ivory, and semiprecious stones) were combined in objects of high artistry.

Ordinary objects for the use of the king and other members of the upper class